Learn Intel VT-x by reversing a CTF challenge

Introduction

Recently, I explored Intel VT-x technology. To deepen my understanding, I took on a CTF challenge focused on reverse-engineering a hypervisor. Documenting this experience will help me solidify and retain what I’ve learned. While this post doesn’t present groundbreaking content beyond what’s already available online, I aim to share my reverse-engineering approach. My goal is to provide a detailed exploration of these topics, making it easy for readers of different knowledge levels to follow.

Two effective ways to retain knowledge are through practical application, like participating in CTFs, and sharing it with others, as I aim to do in this blog post.

The challenge

This challenge is from Flare-On’s 2018 annual CTF.

You can download the challenges here (password: infected).

golf.exe

The description of the challenge is:

How about a nice game of golf? Did you bring a visor? Just kidding, you’re not going outside any time soon. You’re going to be sitting at your computer all day trying to solve this.

Okay, let’s start.

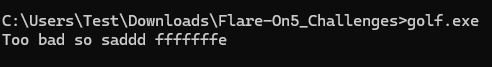

Let’s run golf.exe to observe its behavior.

The program outputs the following message, leaving us with little information on what went wrong:

golf - initial analysis

Before diving into reverse engineering the binary, our initial step involves examining key technical aspects. This includes identifying the compiler used, assessing whether the file is packed, reviewing its imports, uncovering notable strings, and identifying embedded resources.

Identifying packers and anti-analysis techniques early helps determine whether static analysis is sufficient or if dynamic analysis is needed.

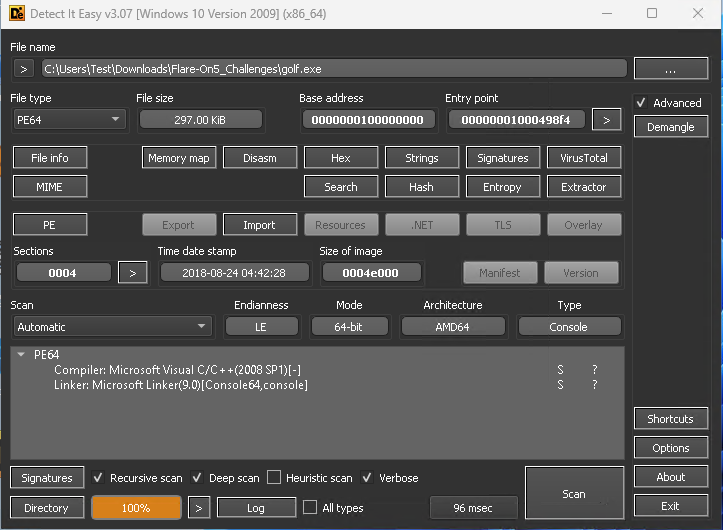

We can load the binary into Detect It Easy (DiE):

The file was compiled with MSVC and is not packed:

Next, let’s examine the imports. Here are some that stand out:

- RegCloseKey, RegCreateKeyExA, RegDeleteKeyA, RegDeleteValueA, RegQueryValueExA, RegSetValueExA - Windows API functions related to registry operations.

- AdjustTokenPrivileges, LookupPrivilegeValueA, OpenProcessToken - Windows API functions related to managing process privileges.

- CreateFileA, DeleteFileA, WriteFile - Windows API functions related to file handling.

- GetCurrentProcess, GetCurrentProcessId, GetCurrentThreadId - Windows API functions are used to obtain information about the current process and threads.

- VirtualAlloc, VirtualFree, VirtualLock, VirtualUnlock - Windows API functions are used for memory management and manipulation.

- GetProcAddress - Windows API function used for dynamically retrieving the address of an exported function or variable from a specified PE.

Lastly, the strings:

- %s@flare-on.com

- C:\fhv.sys

- ErrorControl

- ImagePath

- SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control

- SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\services\fhv

- SeLoadDriverPrivilege

- Start

- SystemStartOptions

- TESTSIGNING

- Too bad so saddd %x

- ZwLoadDriver

- ZwUnloadDriver

- \??\%s\fhv.sys

- \Registry\Machine\System\CurrentControlSet\Services\fhv

- ntdll

- t:\objchk_win7_amd64\amd64\golf.pdb

The most obvious clue from the strings is that the program will likely drop a driver file named fhv.sys onto the disk and then load it. Additionally, we see the strings ZwLoadDriver, and ZwUnloadDriver 1, but they don’t appear in the imports. This indicates they are likely resolved at runtime through the GetProcAddress function, which does appear in the imports.

golf - static analysis

Finding the main function

After loading the binary in IDA Pro, we notice that no symbols are present, indicating the binary has been stripped2. Several methods exist to locate the main function, such as searching for string references and key functions and connecting the dots. Since the compiler used is MSVC, locating the main function is relatively straightforward.

As we saw when running the program earlier in the command prompt, its output was displayed in the console. Checking the IMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADER64.Subsystem confirms this. In console programs, the AddressOfEntryPoint is set to the mainCRTStartup (or wmainCRTStartup) function. An online search for mainCRTStartup can reveal useful information.

mainCRTStartup looks like this:

1

2

3

4

DWORD mainCRTStartup(LPVOID) {

_security_init_cookie();

return _scrt_common_main_seh();

}

Therefore, the first function call to sub_100049B30 corresponds to _security_init_cookie:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

__int64 _security_init_cookie() {

__int64 result; // rax

struct _FILETIME v1; // rbx

unsigned __int64 v2; // rbx

unsigned __int64 v3; // rbx

unsigned __int64 v4; // rbx

LONGLONG v5; // r11

struct _FILETIME SystemTimeAsFileTime; // [rsp+30h] [rbp+8h] BYREF

LARGE_INTEGER PerformanceCount; // [rsp+38h] [rbp+10h] BYREF

SystemTimeAsFileTime = 0 i64;

if (qword_10004B110 == 0x2B992DDFA232 i64) {

GetSystemTimeAsFileTime( & SystemTimeAsFileTime);

v1 = SystemTimeAsFileTime;

v2 = GetCurrentProcessId() ^ * (unsigned __int64 * ) & v1;

v3 = GetCurrentThreadId() ^ v2;

v4 = GetTickCount() ^ v3;

QueryPerformanceCounter( & PerformanceCount);

v5 = (v4 ^ PerformanceCount.QuadPart) & 0xFFFFFFFFFFFF i64;

result = 0x2B992DDFA233 i64;

if (v5 == 0x2B992DDFA232 i64)

v5 = 0x2B992DDFA233 i64;

qword_10004B110 = v5;

qword_10004B118 = ~v5;

} else {

result = ~qword_10004B110;

qword_10004B118 = ~qword_10004B110;

}

return result;

}

We can confirm this again by searching online—this time for the constant 0x2B992DDFA232, which provides promising results. We can apply the same method to the next function, sub_100049668 (__scrt_common_main). After some basic reverse engineering, we identified that the main function is sub_100001C10.

main

First, argv[1] must be exactly 0x18 bytes long.

Next, there is a call to sub_100001A60, which performs the following tasks:

Calls

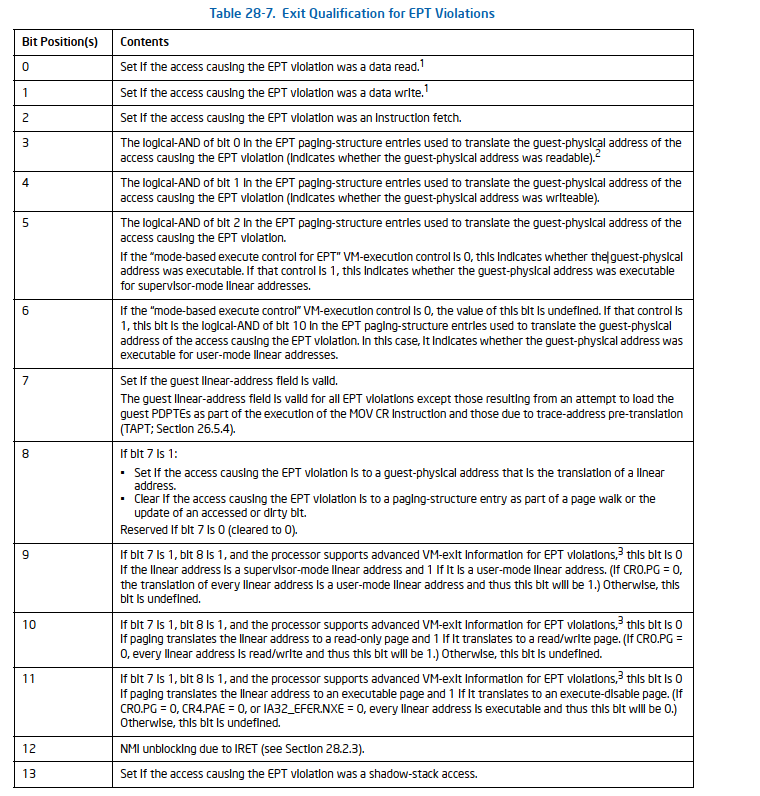

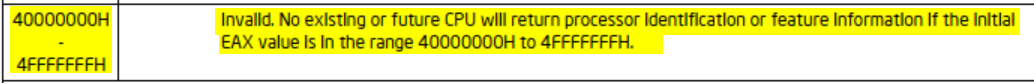

sub_100001A73to executeCPUIDwithEAXset to0x40000001and perform a calculation based on the result of theEAXregister. What information does0x40000001provide? Searching for0x40000001in the Intel SDM yields no results. Although theCPUIDdocumentation provides some context, it doesn’t directly answer the question:

Again, searching forCPUID 0x40000001online can provide us with the answer.

The calculation routine (sub_1000014C0) takes a DWORD array (dword_10004B140) as an argument. This array contains constant values, which, after a quick search, are found to be used for a CRC32 checksum. The CRC32 result is then compared with the hardcoded value0x5C139D95. If they do not match, the program proceeds as usual. The purpose of this check is currently unknown. While there could be several reasons for it, the important thing is that it does not impede our progress, so we can disregard it for now. Additionally, since the input is based onEAX(4-byte value), we can attempt all possible inputs (0x00000000-0xFFFFFFFF) to find the “correct” input that matches the check.Calls

sub_100001590to check whether the TESTSIGNING mode is enabled; if so, proceed with execution.Calls

sub_1000021C0to dump the embedded driver file toC:\fhv.sys.

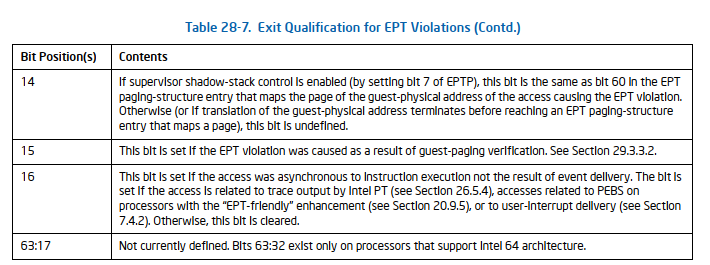

NOTE: If you attempt to use the decompiler or view thesub_1000021C0function in graph mode, you will encounter an error stating “too big function” or “Sorry, this node is too big to display”. This happens because thefhv.sysfile is stored as an array on the stack, which significantly increases the size of the function. A workaround for the decompilation can be found here. For the graph view, click the button shown in the following figure:

To extract thefhv.sysbinary, we can let the program do the job for us and dump it to the disk.Calls

sub_100001700to resolve the ZwLoadDriver function using GetProcAddress, adjust the current process privileges to includeSeLoadDriverPrivilege, register the new driver in the registry, and finally callZwLoadDriverto load the driver.

Returning to the main function, the next step is to allocate a buffer using VirtualAlloc. This buffer is allocated with read, write, and execute permissions. Subsequently, 0x1C bytes are copied from unk_10004B120 to the allocated buffer (lpAddress), followed by four function calls. Each function receives an offset from our argv[1] and a pointer to the allocated buffer:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

int __fastcall main(int argc, const char ** argv, const char ** envp) {

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

lpAddress = VirtualAlloc(NULL, 0x1000, MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

if (!lpAddress ||

(qmemcpy(lpAddress, & unk_10004B120, 0x1C), sub_100001E40(argv[1], lpAddress)) &&

sub_100001F20(argv[1] + 5, lpAddress) &&

sub_100002000(argv[1] + 0xE, lpAddress) &&

sub_1000020E0(argv[1] + 0x13, lpAddress))

{

ret = 0;

}

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

if (ret)

printf("Too bad so saddd %x\n", ret);

else

printf("%s@flare-on.com\n", argv[1]);

return ret;

}

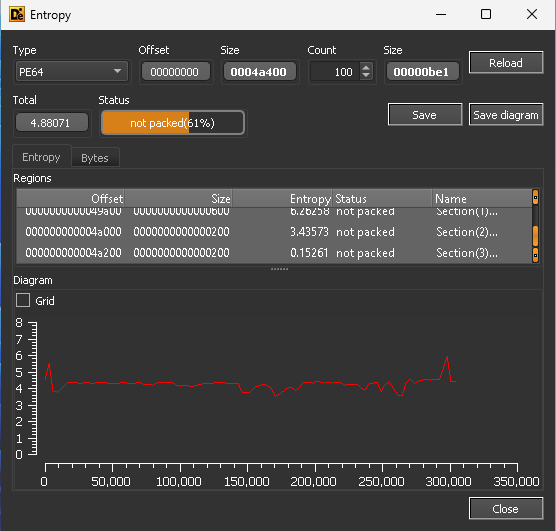

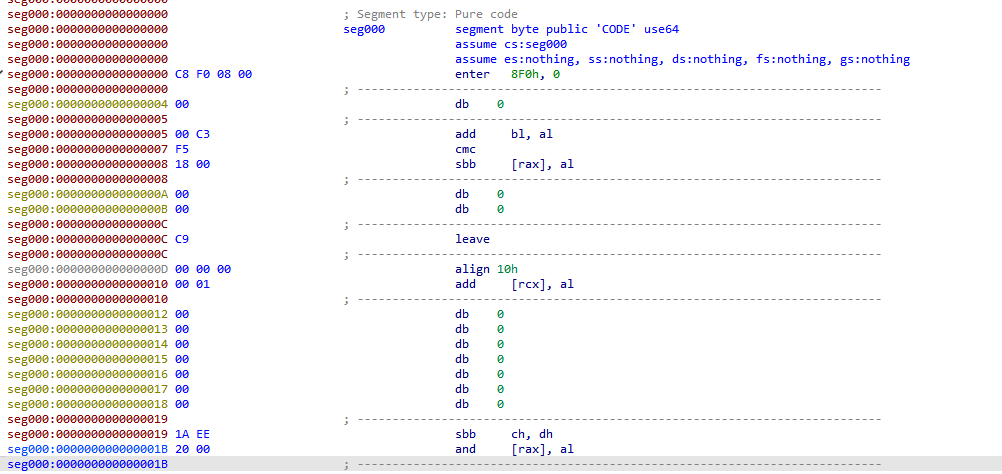

Since the lpAddress buffer is allocated with read, write, and execute permissions, it’s a strong indication that it likely holds executable code. Therefore, we can try disassembling unk_10004B120 to examine its contents:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

.data:000000010004B120 sub_10004B120 proc near ; DATA XREF: sub_100001C10+106↑o

.data:000000010004B120 vmcall

.data:000000010004B123 jz short loc_10004B133

.data:000000010004B125 jb short loc_10004B12B

.data:000000010004B127 xor rax, rax

.data:000000010004B12A retn

.data:000000010004B12B ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

.data:000000010004B12B

.data:000000010004B12B loc_10004B12B: ; CODE XREF: sub_10004B120+5↑j

.data:000000010004B12B mov rax, 2

.data:000000010004B132 retn

.data:000000010004B133 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

.data:000000010004B133

.data:000000010004B133 loc_10004B133: ; CODE XREF: sub_10004B120+3↑j

.data:000000010004B133 mov rax, 1

.data:000000010004B13A retn

.data:000000010004B13A sub_10004B120 endp

.data:000000010004B13A

.data:000000010004B13A ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

.data:000000010004B13B db 0

.data:000000010004B13C db 0EFh

Additionally, we can verify this by examining the four function calls, which each make a call into the

lpAddressbuffer.

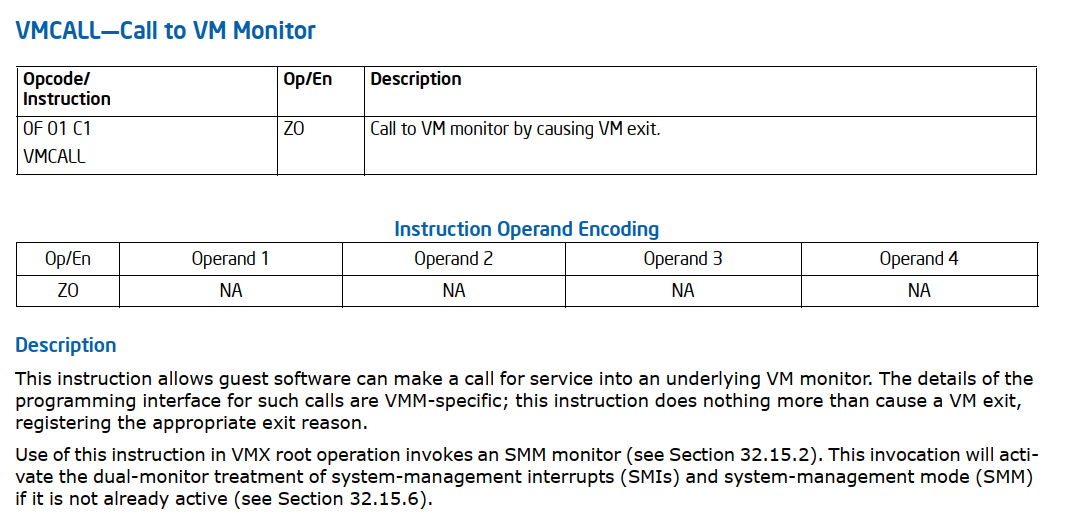

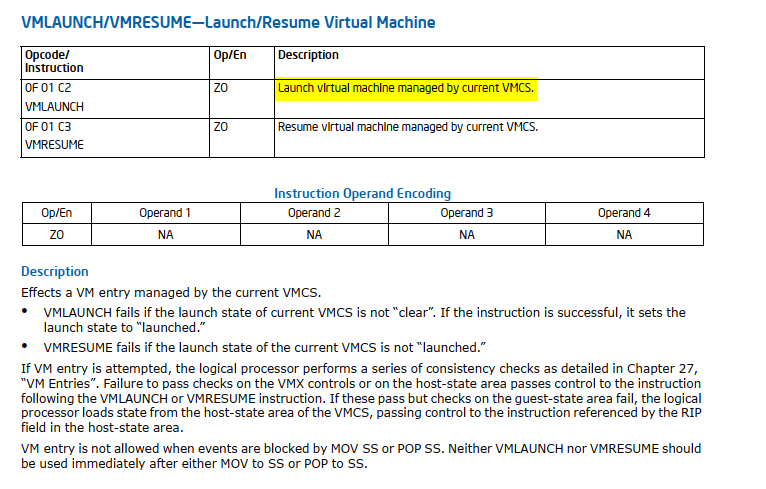

The first instruction is a special one called VMCALL. What does the VMCALL instruction do? Let’s refer to the Intel SDM again.

VMCALL

But what does “Call to VM monitor by causing VM exit” mean? Now, it’s time to dive into hypervisors.

Hypervisors

Before we continue, I want to clarify that this post is not intended to teach hypervisor development, as there are many excellent guides available for that. Instead, this post will focus on understanding hypervisors from a reverse-engineering perspective. In addition, Intel VT-x technology is vast, so I’ll cover only the essential aspects needed for this challenge.

Disclosure: I used ChatGPT to write some non-technical parts about hypervisors.

What is a Hypervisor?

A hypervisor, also known as a Virtual Machine Monitor (VMM), is software that creates and manages virtual machines (VMs) on a host system. It enables multiple operating systems to run concurrently on a single physical machine by abstracting hardware resources and providing each VM with its own virtualized environment. Modern hypervisors leverage hardware extensions such as Intel VT-x and AMD-V to enhance performance and security by providing efficient virtualization capabilities directly supported by the CPU.

Types of Hypervisors

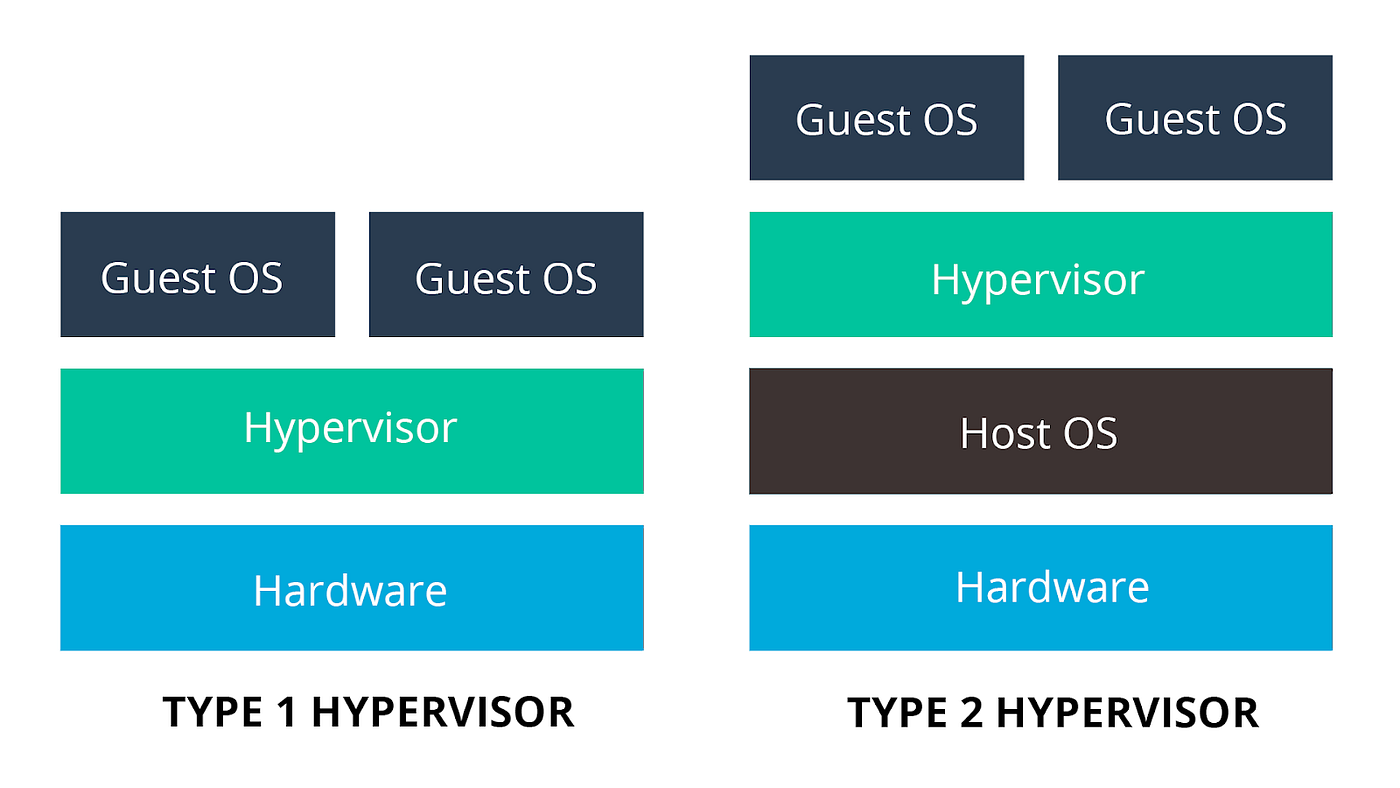

There are two types of hypervisors: Type 1, also known as native or bare-metal hypervisors, and Type 2, commonly called hosted hypervisors.

Type 1 Hypervisors (Bare-Metal)

- Definition: Run directly on the host’s hardware to manage guest operating systems, without requiring a host OS.

- Examples: VMware ESXi, Microsoft Hyper-V, Xen.

- Characteristics: High performance, efficient, commonly used in enterprise environments, and more secure due to a minimalistic hypervisor layer.

Type 2 Hypervisors (Hosted)

- Definition: Run on a conventional operating system as a software layer or application.

- Examples: VMware Workstation, Oracle VM VirtualBox, Parallels Desktop.

- Characteristics: Easier to set up, suitable for personal use, development, and testing, though slightly less efficient due to the overhead of the host OS.

As you’ve probably noticed, our challenge runs on top of the operating system, making it a type 2 hypervisor.

Core Components of Intel VT-x

Intel VT-x is a set of hardware extensions that provide robust support for virtualization. It enables efficient creation and management of virtual machines by providing features that enhance performance and security.

In the following sections, we will cover the key aspects of Intel VT-x.

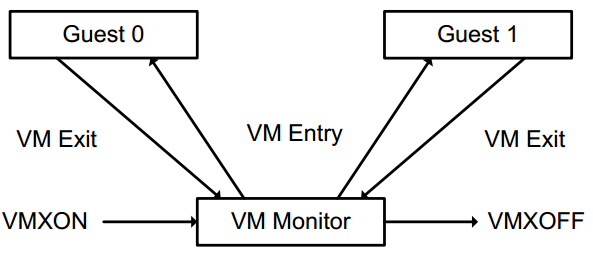

VMX - Virtual Machine Extensions

VMX is a set of instructions that enable virtualization on Intel processors. It introduces new CPU operation modes that facilitate the management of virtual machines. The two primary modes are VMX root mode (for the hypervisor) and VMX non-root mode (for guest VMs).

Let’s examine the most relevant VMX instructions for this post:

| Intel Mnemonic | Description | Entering mode |

|---|---|---|

| VMXON | Enter VMX Operation | VMX root mode |

| VMXOFF | Leave VMX Operation | |

| VMCLEAR | Clear Virtual-Machine Control Structure | |

| VMPTRLD | Load Pointer to Virtual-Machine Control Structure | |

| VMREAD | Read Field from Virtual-Machine Control Structure | |

| VMWRITE | Write Field to Virtual-Machine Control Structure | |

| VMLAUNCH | Launch Virtual Machine | VMX non-root mode |

| VMRESUME | Resume Virtual Machine | VMX non-root mode |

| VMCALL | Call to VM Monitor | VMX root mode |

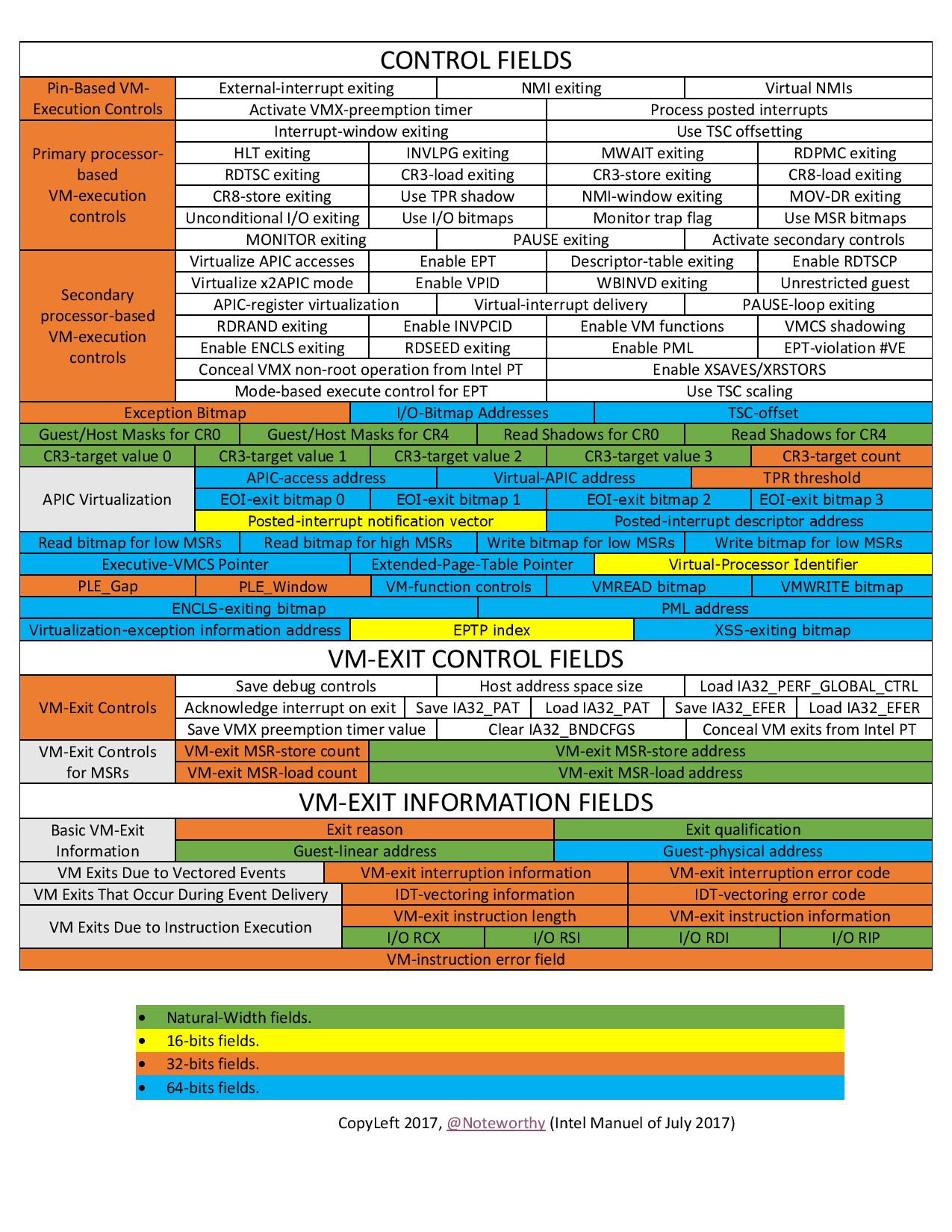

VMCS - Virtual Machine Control Structure

The VMCS is a crucial data structure in Intel VT-x that controls the behavior of virtual machines. It stores state information for the guest and the hypervisor, managing transitions between them.

The VMCS includes fields for:

- Guest-State Area: Stores (saves) the state of the guest VM (e.g., segment registers, control registers) when the VM is not running, i.e., during a VM-exit.

- Host-State Area: Stores the state of the hypervisor (host) to be loaded when the guest VM exits.

- VM-Execution Control Fields: Configure how the guest VM operates, specifying which events and instructions cause VM exits.

- VM-Exit Control Fields: Define the conditions under which the processor exits from the guest VM to the hypervisor.

- VM-Entry Control Fields: Manage the conditions for entering a guest VM from the hypervisor.

There is a picture that illustrates and catalogs VMCS fields in a cool way:

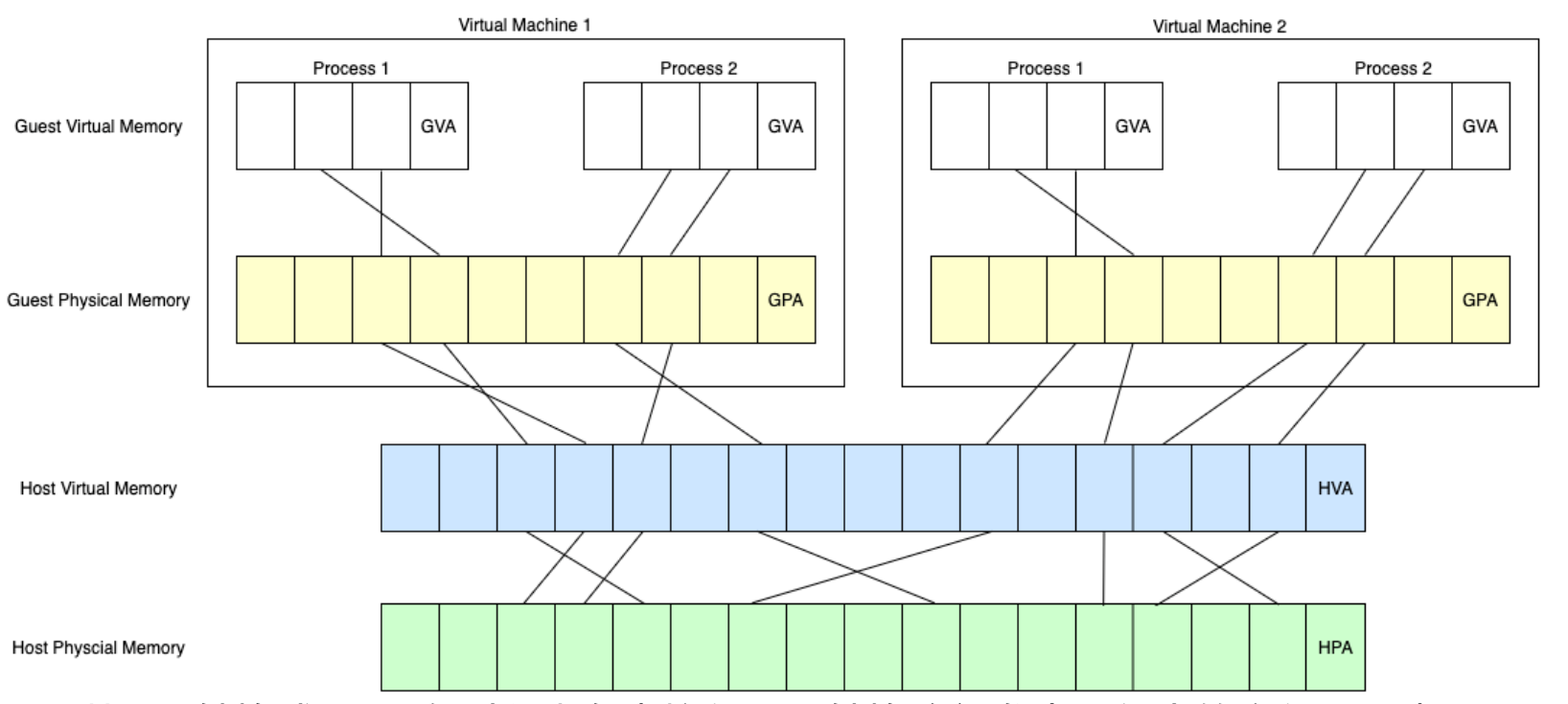

Extended Page Tables (EPT) and Virtual Processor ID (VPID)

Extended Page Tables (EPT) is a hardware-assisted memory virtualization feature that offers a Second Level of Address Translation (SLAT). It maps guest physical addresses to host physical addresses, enabling the hypervisor to manage memory more efficiently and securely. EPT reduces the overhead associated with traditional software-based memory management techniques.

Virtual Processor ID (VPID) is a feature that assigns unique identifiers to each virtual processor, enabling the processor to maintain separate caches for each VM. This minimizes the overhead of cache flushing during VM switches and enhances performance.

This may seem complex for those without prior experience with Intel VT-x, but don’t worry—you don’t need to remember everything. Things will become clearer in the upcoming sections.

fhv.sys

fhv - initial analysis

The file is compiled with MSVC and the file is not packed.

Let’s examine the imports. Here are some that stand out:

-

WdfVersionBind,

WdfVersionBindClass, WdfVersionUnbind,WdfVersionUnbindClass- Part of the Windows Driver Frameworks (WDF). - MmAllocateContiguousMemory, MmFreeContiguousMemory, MmGetPhysicalAddress, MmGetPhysicalMemoryRanges, MmGetVirtualForPhysical - These functions are part of the Windows kernel-mode memory management routines.

-

MmGetSystemRoutineAddress - Windows kernel-mode function used to retrieve the address of a system routine (function) given its name.

MmGetSystemRoutineAddressandGetProcAddressserve similar purposes in different contexts. -

RtlCompareMemory, strcmp -

RtlCompareMemoryandstrcmpare functions used for comparing memory and strings, respectively. -

KdDebuggerNotPresent, RtlGetVersion -

KdDebuggerNotPresentchecking the presence of a kernel debugger, andRtlGetVersionis used for retrieving the operating system version information.

Lastly, the strings found within the binary:

- KmdfLibrary

- ASDASDASDASDASDASDASDASDASDASDASDASDASDASDASDASDASDASDASDASDASD\toobadsoosadd.pdb

This is a KMDF driver. We won’t delve into the differences between WDM and WDF or the methods for reverse-engineering KMDF drivers, as there are many resources available that cover these topics.

fhv - static analysis

FxDriverEntry

The only noteworthy part of FxDriverEntry is its call to sub_14000D000.

sub_14000D000

- Calls

sub_14000D0E4to check if the operating system is Windows Vista or newer, based on RtlGetVersion output:1 2 3 4 5 6 7

bool sub_14000D0E4() { struct _OSVERSIONINFOW VersionInformation; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-138h] BYREF memset(&VersionInformation, 0, sizeof(VersionInformation)); // dwMajorVersion 6 = Windows Vista and up return RtlGetVersion(&VersionInformation) >= 0 && ((VersionInformation.dwMajorVersion - 6) & -5) == 0; }

- Calls

sub_14000D180andsub_14000B73C; details on these will be provided in the next sections. - Calls

sub_14000D0BAwith0x13687456as an argument, which is then passed tosub_140002F9Eto execute aVMCALLinstruction. After reviewingsub_14000D180,sub_14000B73C, and their subroutines, we will revisitsub_14000D0BA.

sub_14000D180

sub_14000D180 begins with a call to RtlGetVersion, followed by a condition that checks whether the system matches a specific build version:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

NTSTATUS __fastcall sub_14000D180(__int64 a1) {

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

VersionInformation.dwOSVersionInfoSize = 0x114;

memset(&VersionInformation.dwMajorVersion, 0, 0x11064);

ntstatus = RtlGetVersion(&VersionInformation);

if (VersionInformation.dwMajorVersion < 10 || VersionInformation.dwBuildNumber < 14316) // [1]

{

qword_140008C50 = qword_140007000; // [2]

qword_140008C58 = qword_140007008;

qword_140008C60 = qword_140007010;

qword_140008C68 = qword_140007018;

} else {

pfn_MmGetVirtualForPhysical = (char *)wrap_MmGetSystemRoutineAddress(L"MmGetVirtualForPhysical"); // [3]

if (!pfn_MmGetVirtualForPhysical) return STATUS_PROCEDURE_NOT_FOUND;

v5 = wrapper_RtlCompareMemory(pfn_MmGetVirtualForPhysical, 0x30, &unk_140006150, 0xA); // [4]

if (!v5) return STATUS_PROCEDURE_NOT_FOUND;

qword_140008C68 = *(_QWORD *)(v5 + 0xA); // [5]

v6 = ((unsigned __int64)qword_140008C68 >> 0x27) & 0x1FF; // [6]

qword_140008C58 = qword_140008C68 | (v6 << 0x1E) | (v6 << 0x15); // [7]

qword_140008C50 = qword_140008C58 | (v6 << 0xC); // [8]

qword_140008C60 = qword_140008C68 | (v6 << 0x1E); // [9]

}

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

}

At [1], the condition checks whether the OS build is less than 14316. If the condition is met, the code in [2] is executed. An online search reveals that build 14316 corresponds to the Windows 10 Anniversary Update (also known as version 1607, codenamed Redstone 1). At [2], the code initializes four global variables based on the values of four other global variables. Let’s examine the values of qword_140007000, qword_140007008, qword_140007010, and qword_140007018:

1

2

3

4

.data:0000000140007000 qword_140007000 dq 0FFFFF6FB7DBED000h ; DATA XREF: sub_14000D180:loc_14000D270↓r

.data:0000000140007008 qword_140007008 dq 0FFFFF6FB7DA00000h ; DATA XREF: sub_14000D180+104↓r

.data:0000000140007010 qword_140007010 dq 0FFFFF6FB40000000h ; DATA XREF: sub_14000D180+112↓r

.data:0000000140007018 qword_140007018 dq 0FFFFF68000000000h ; DATA XREF: sub_14000D180+120↓r

For those with familiarity and experience in Windows Internals and Windows kernel exploitation, these values will be familiar. However, for those who are not, a quick online search for these values will provide clarity. Those values are important constants related to the Windows memory management system, specifically for the paging structures in 64-bit Windows. So according to those values we can rename qword_140007000, qword_140007008, qword_140007010, and qword_140007018 to: g_PML4_BASE_before_rs1, g_PDP_BASE__before_rs1, g_PD_BASE_before_rs1, g_PT_BASE_before_rs1, respectively.

What’s special about the Windows 10 Anniversary Update? It turns out that in this version, Microsoft decided to place the paging structures at random addresses.

Now let’s see what happens if our OS build is greater than 14316 build.

The code at [3] retrieves the address of MmGetVirtualForPhysical. Then, at [4], it calls wrapper_RtlCompareMemory (sub_140002EF8), which compares the bytes from MmGetVirtualForPhysical with those from unk_140006150 and returns the number of bytes that match until the first difference.

Let’s examine the disassembly of unk_140006150:

1

2

3

4

5

.rdata:0000000140006150 48 8B 04 D0 mov rax, [rax+rdx*8]

.rdata:0000000140006154 48 C1 E0 19 shl rax, 19h

.rdata:0000000140006154 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

.rdata:0000000140006158 48 db 48h ; H

.rdata:0000000140006159 BA db 0BAh

Now let’s open ntoskrnl.exe in IDA, and examine the disassembly of MmGetVirtualForPhysical:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

.text:00000001403B1C20 ; PVOID __stdcall MmGetVirtualForPhysical(PHYSICAL_ADDRESS PhysicalAddress)

.text:00000001403B1C20 public MmGetVirtualForPhysical

.text:00000001403B1C20 MmGetVirtualForPhysical proc near ; DATA XREF: .pdata:00000001400E79C8↑o

.text:00000001403B1C20 48 8B C1 mov rax, rcx

.text:00000001403B1C23 48 C1 E8 0C shr rax, 0Ch

.text:00000001403B1C27 48 8D 14 40 lea rdx, [rax+rax*2]

.text:00000001403B1C2B 48 03 D2 add rdx, rdx

.text:00000001403B1C2E 48 B8 08 00 00 00 00 DE mov rax, 0FFFFDE0000000008h

.text:00000001403B1C2E FF FF

.text:00000001403B1C38 48 8B 04 D0 mov rax, [rax+rdx*8]

.text:00000001403B1C3C 48 C1 E0 19 shl rax, 19h

.text:00000001403B1C40 48 BA 00 00 00 00 80 F6 mov rdx, 0FFFFF68000000000h

.text:00000001403B1C40 FF FF

.text:00000001403B1C4A 48 C1 E2 19 shl rdx, 19h

.text:00000001403B1C4E 81 E1 FF 0F 00 00 and ecx, 0FFFh

.text:00000001403B1C54 48 2B C2 sub rax, rdx

.text:00000001403B1C57 48 C1 F8 10 sar rax, 10h

.text:00000001403B1C5B 48 03 C1 add rax, rcx

.text:00000001403B1C5E C3 retn

.text:00000001403B1C5E MmGetVirtualForPhysical endp

The wrapper_RtlCompareMemory function returns the address of the matching pattern, which in this case is the instruction mov rax, [rax+rdx*8] within MmGetVirtualForPhysical. At [5], it adds 0xA to this address, extracts a qword from the resulting address, and stores it in qword_140008C68 (g_PT_BASE). Essentially, the code is trying to extract the value 0xFFFFF68000000000 from the instruction mov rdx, 0FFFFF68000000000h. However, the actual value may vary at runtime due to the page table randomization mitigation introduced by the Windows 10 Anniversary Update. Between [6] and [9], the code then constructs the rest of the paging structure base addresses based on the PT_BASE value.

Next, sub_14000D180 calls sub_14000D36C. This function creates a custom data structure mapping the system’s physical memory layout, which is then used to configure EPT structures—details of which are outside the scope of this post.

Why is

sub_14000D180covered? Spoiler alert:

The global variables initialized by this function (e.g.,g_PML4_BASE) are not actively used. The function is discussed here because it provides valuable insights into reverse engineering methodology, touching on Windows internals and kernel exploitation. Gaining experience enhances your ability to recognize patterns and constants more readily. The approach shown for identifying memory addresses of paging data structures by pattern matching is applied in real-world exploits. By using kernel read primitives, these addresses can be leaked, enabling the calculation of Virtual Address (VA) to Page Table Entry (PTE) mappings, which then can be used for PTE manipulation attacks.

sub_14000B73C

As we dive deeper, this function reveals some of its most intriguing aspects:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

NTSTATUS sub_14000B73C() {

__int64 result; // rax

__int64 v16; // rdx

char v17; // bl

__int64 v18; // rbx

unsigned int v19; // ebx

_RAX = 1;

__asm { cpuid } // [1]

if ((int)_RCX < 0) { // [2]

_RAX = 0x40000001; // [3]

__asm { cpuid }

if ((_DWORD)_RAX == 0x56484C46) // [4]

return STATUS_CANCELLED;

}

_RAX = 1;

__asm { cpuid } // [5]

if ((_RCX & 0x20) == 0) // [6]

return STATUS_HV_FEATURE_UNAVAILABLE;

if ((((sub_140002F80(0x480) >> 0x20) >> 0x12) & 0xF) != 6) // [7]

return STATUS_HV_FEATURE_UNAVAILABLE;

v17 = sub_140002F80(0x3A); // [8]

if ((v17 & 1) == 0 && sub_14000B624(sub_14000BDE0, 0) < 0) // [9]

return STATUS_HV_FEATURE_UNAVAILABLE;

if ((v17 & 4) == 0 || !sub_14000B5A4()) // [10]

return STATUS_HV_FEATURE_UNAVAILABLE;

v18 = sub_14000BAC4(); // [11]

if (!v18)

return STATUS_MEMORY_NOT_ALLOCATED;

sub_14000B330(); // [12]

result = sub_14000B624(sub_14000C614, v18); // [13]

v19 = result;

if (result < STATUS_SUCCESS) {

sub_14000B624(sub_14000C638, 0); // [14]

return v19;

}

return result;

}

From this point forward, the Intel SDM - Volume 3 (3A, 3B, 3C & 3D): System Programming Guide will be our primary reference.

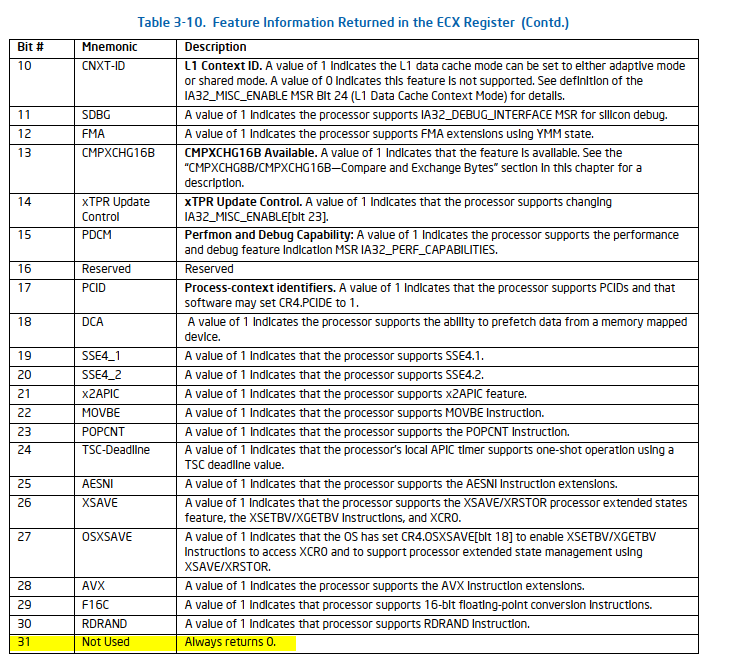

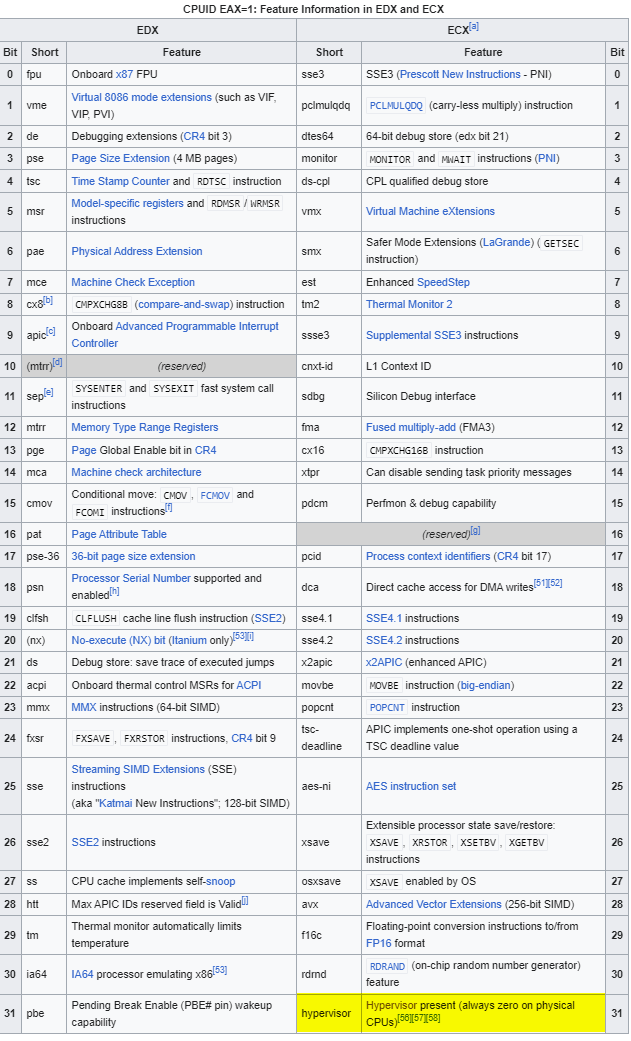

At [1], the code executes CPUID with EAX set to 1, and then at [2], it checks whether RCX is negative. This check essentially means, ‘Is the MSB set?’ The CPUID - Initial EAX Value = 1 documentation in the SDM provides some information, though it doesn’t necessarily bring us closer to the answer:

Again, searching for CPUID 1 online can provide us with the answer:

If the hypervisor present bit is set, the code at [3] and [4] will be executed. At [3], CPUID is executed again with EAX set to 0x40000001, which we’ve already seen in golf!sub_100001A73. At [4], it checks if EAX equals 0x56484C46 (VHLF), and if true, the function will abort with STATUS_CANCELLED. We can infer that the test in golf!sub_100001A73 likely uses the CPUID input value of 0x56484C46, causing the condition to be true. This test seems to confirm whether the driver has already been executed and initialized. If the driver is loaded again, this code will prevent it from running again the initialization code.

Next, at [5], the CPUID instruction is executed again with EAX set to 1. Then, at [6], it checks whether the 5th bit of RCX is unset. Let’s refer to the SDM for more details:

Additionally, the Introduction to Virtual Machine Extensions chapter includes a section called Discovering Support for VMX that describes this process in detail:

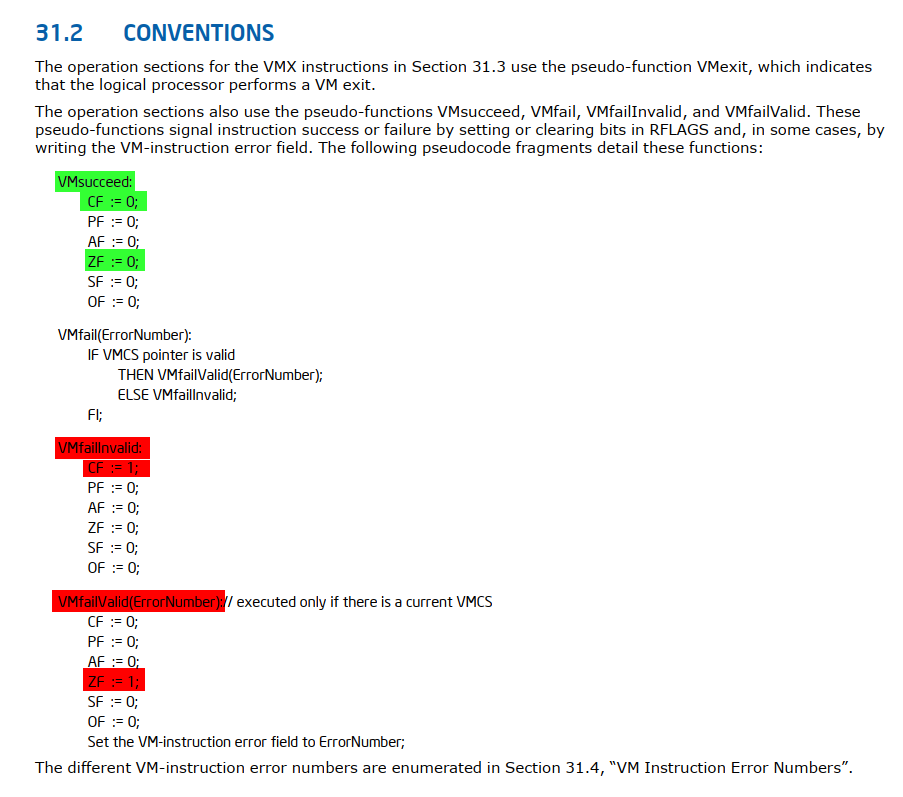

DISCOVERING SUPPORT FOR VMX

Before system software enters into VMX operation, it must discover the presence of VMX support in the processor.

System software can determine whether a processor supports VMX operation using CPUID. If CPUID.1:ECX.VMX[bit 5] = 1, then VMX operation is supported. See Chapter 3, “Instruction Set Reference, A-L” of Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual, Volume 2A.

The VMX architecture is designed to be extensible so that future processors in VMX operation can support additional features not present in first-generation implementations of the VMX architecture. The availability of extensible VMX features is reported to software using a set of VMX capability MSRs (see Appendix A, “VMX Capability Reporting Facility”).

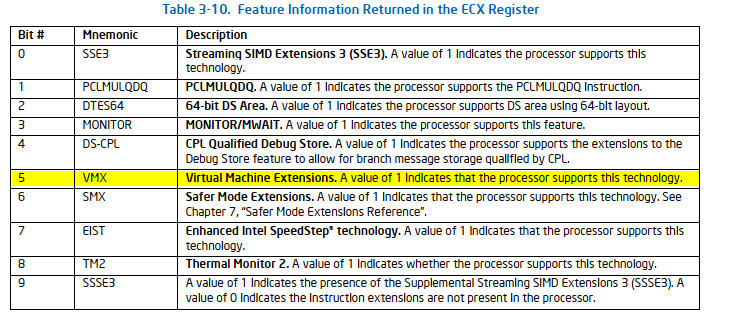

Next, at [7] and [8] there is a call to sub_140002F80, let’s take a look at sub_140002F80:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

.text:0000000140002F80 ; unsigned __int64 __fastcall sub_140002F80(unsigned int)

.text:0000000140002F80 sub_140002F80 proc near ; CODE XREF: sub_140003144+D8↓p

.text:0000000140002F80 ; sub_140003144+E5↓p ...

.text:0000000140002F80 0F 32 rdmsr

.text:0000000140002F82 48 C1 E2 20 shl rdx, 20h

.text:0000000140002F86 48 0B C2 or rax, rdx

.text:0000000140002F89 C3 retn

.text:0000000140002F89 sub_140002F80 endp

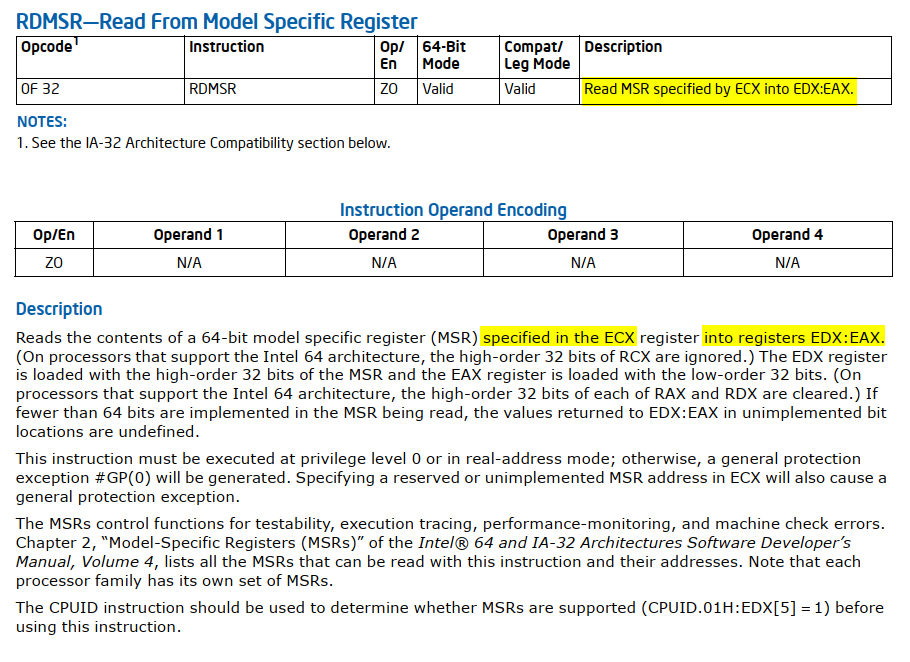

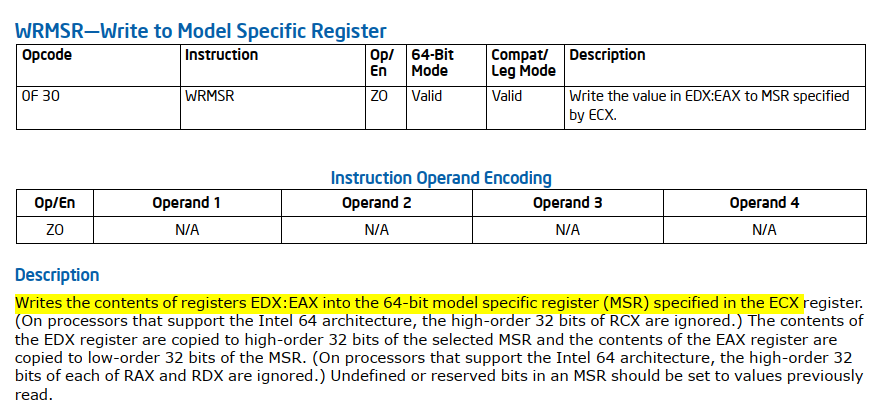

RDMSR reads the value stored in a Model-Specific Register (MSR):

A model-specific register (MSR) is a type of control register in the x86 system architecture. MSRs are used for tasks such as debugging, program execution tracing, computer performance monitoring, and controlling specific CPU features.

The function sub_140002F80 reads the contents of the MSR specified by the ECX register and returns the result in RAX. To make the code easier to follow, we can rename sub_140002F80 to readmsr. Now that it’s clear sub_140002F80 (readmsr) takes an MSR as a parameter, we can simplify future work by importing a header file containing an enum of MSR values (you can use this one). Additionally, we can update the type declaration of sub_140002F80 (readmsr) to improve the clarity of the decompiled code.

Now we can revisit the code at [7] and [8].

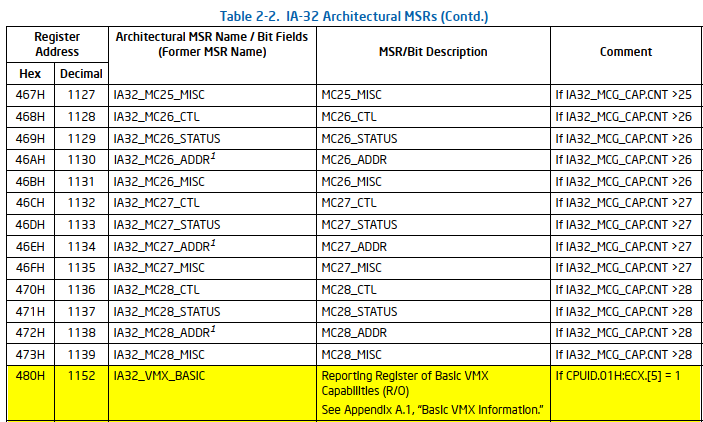

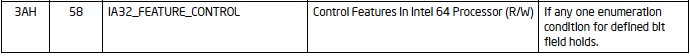

At [7], the value 0x480 is passed as an argument to sub_140002F80 (readmsr). What does 0x480 represent? The SDM provides the answer:

At [7] the code verifies if the memory type of the IA32_VMX_BASIC MSR is set to Write Back (WB). We won’t go into the details of memory type here. For those interested in learning more, Daax’s excellent blog post offers a detailed explanation.

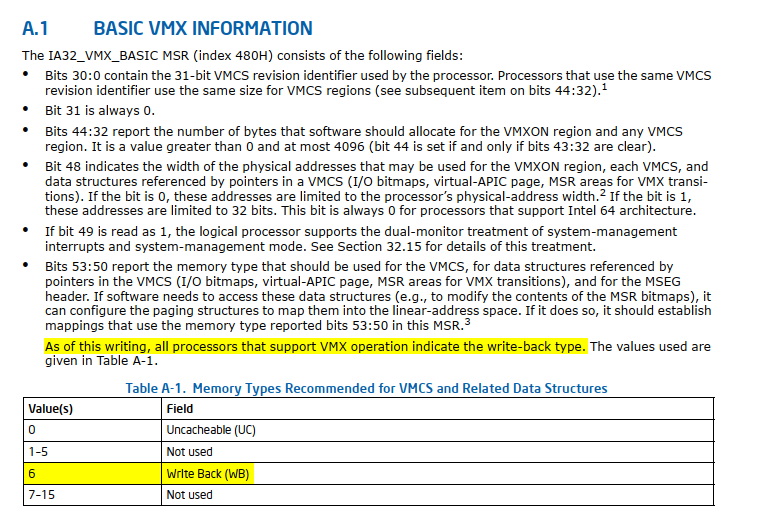

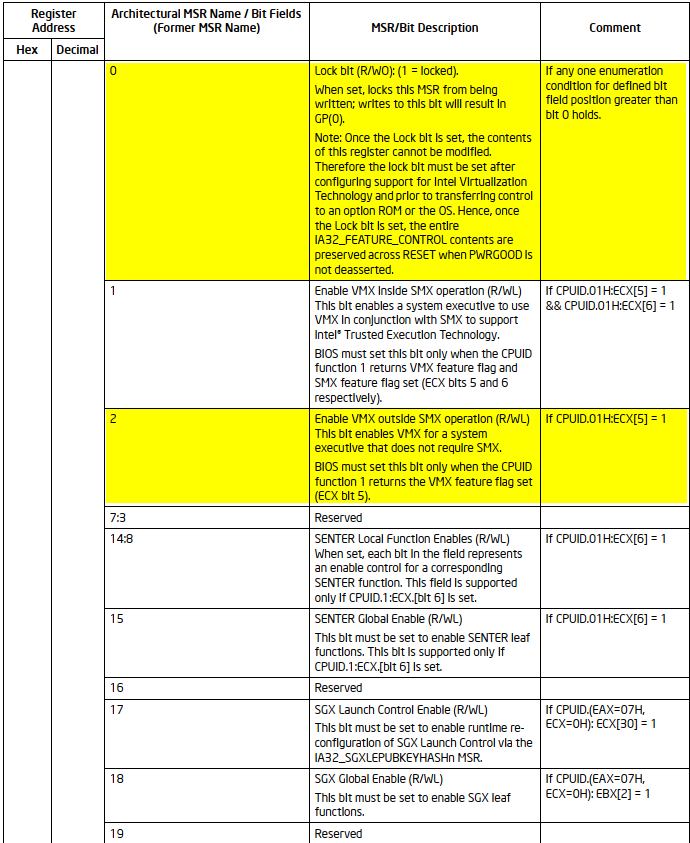

At [8], the value 0x3A is passed as an argument to sub_140002F80 (readmsr):

At [9] and [10] the code checks if bits 0 and 2 of IA32_FEATURE_CONTROL MSR are cleared. The chapter Introduction to Virtual Machine Extensions describes this process in detail, specifically in the section titled Enabling and Entering VMX Operation:

ENABLING AND ENTERING VMX OPERATION

Before system software can enter VMX operation, it enables VMX by setting CR4.VMXE[bit 13] = 1. VMX operation is then entered by executing the VMXON instruction. VMXON causes an invalid-opcode exception (#UD) if executed with CR4.VMXE = 0. Once in VMX operation, it is not possible to clear CR4.VMXE (see Section 24.8). System software leaves VMX operation by executing the VMXOFF instruction. CR4.VMXE can be cleared outside of VMX operation after executing of VMXOFF.

VMXON is also controlled by the IA32_FEATURE_CONTROL MSR (MSR address 3AH). This MSR is cleared to zero when a logical processor is reset. The relevant bits of the MSR are:

- Bit 0 is the lock bit. If this bit is clear, VMXON causes a general-protection exception. If the lock bit is set, WRMSR to this MSR causes a general-protection exception; the MSR cannot be modified until a power-up reset condition. System BIOS can use this bit to provide a setup option for BIOS to disable support for VMX. To enable VMX support in a platform, BIOS must set bit 1, bit 2, or both (see below), as well as the lock bit.

- Bit 1 enables VMXON in SMX operation. If this bit is clear, execution of VMXON in SMX operation causes a general-protection exception. Attempts to set this bit on logical processors that do not support both VMX operation (see Section 24.6) and SMX operation (see Chapter 7, “Safer Mode Extensions Reference,” in Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual, Volume 2D) cause general-protection exceptions.

- Bit 2 enables VMXON outside SMX operation. If this bit is clear, execution of VMXON outside SMX operation causes a general-protection exception. Attempts to set this bit on logical processors that do not support VMX operation (see Section 24.6) cause general-protection exceptions.

Additionally, at [9], [13], and [14], the code calls the function sub_14000B624, which takes two parameters. Let’s examine sub_14000B624:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

NTSTATUS __fastcall sub_14000B624(__int64(__fastcall *a1)(__int64), __int64 a2) {

ULONG v4; // ebx

ULONG ActiveProcessorCount; // edi

NTSTATUS result; // eax

int v7; // esi

struct _PROCESSOR_NUMBER ProcNumber; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-30h] BYREF

struct _GROUP_AFFINITY Affinity; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-28h] BYREF

struct _GROUP_AFFINITY PreviousAffinity; // [rsp+38h] [rbp-18h] BYREF

v4 = 0;

ActiveProcessorCount = KeQueryActiveProcessorCountEx(ALL_PROCESSOR_GROUPS); // [1]

if (!ActiveProcessorCount)

return STATUS_SUCCESS;

while (TRUE) { // [2]

ProcNumber = 0;

result = KeGetProcessorNumberFromIndex(v4, &ProcNumber); // [4]

if (result < STATUS_SUCCESS)

break;

*(_QWORD *)&Affinity.Group = ProcNumber.Group;

Affinity.Mask = 1 << ProcNumber.Number;

PreviousAffinity.Mask = 0;

*(_QWORD *)&PreviousAffinity.Group = 0;

KeSetSystemGroupAffinityThread(&Affinity, &PreviousAffinity); // [5]

v7 = a1(a2); // [6]

KeRevertToUserGroupAffinityThread(&PreviousAffinity);

if (v7 < STATUS_SUCCESS)

return v7;

if (++v4 >= ActiveProcessorCount) // [3]

return STATUS_SUCCESS;

}

return result;

}

At [1], the function queries the number of active logical processors in the system by calling KeQueryActiveProcessorCountEx. This sets up the loop boundary for processing all logical processors. At [2], the function enters a loop that will continue until all logical processors have been processed or an error occurs. At [3], at the end of each loop iteration, the function checks if all logical processors have been processed. If so, it returns STATUS_SUCCESS.

At [4], for each logical processor, the function retrieves the logical processor number and group information by calling KeGetProcessorNumberFromIndex. This allows the function to target specific logical processors. Next, at [5], the function sets the thread affinity to run on the specific logical processor using KeSetSystemGroupAffinityThread. This ensures that the subsequent code runs on the intended logical processor. Next, at [6], the function calls the provided function pointer a1 with the argument a2. This is the core operation that is being performed on each logical processor. After executing the provided function, the thread’s affinity is reverted to its previous state by calling KeRevertToUserGroupAffinityThread.

In summary, sub_14000B624 iterates through all active logical processors in the system and executes a provided function (a1) (with a2 as the argument) on each logical processor.

Why is it necessary to run a specific function on all logical processors rather than just one? We will uncover the answer in the following sections.

Later, we will examine the functions sub_14000BDE0, sub_14000C614, and sub_14000C638 that are called by sub_14000B624 (run_function_on_all_logical_processors). But first we will continue with sub_14000B624.

At [10], the function sub_14000B5A8 calls readmsr with IA32_VMX_EPT_VPID_CAP (MSR 0x48C) as an argument and checks the return value IA32_VMX_EPT_VPID_CAP. At [12], there is a call to sub_14000B330 which deals with Memory type range registers (MTRRs). We won’t go into detail about EPT & MTRR in this post. However, those interested can read the materials in the Recommended Reading section.

Back now to [11], we will examine sub_14000BAC4:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

PVOID sub_14000BAC4() {

PVOID buf_1; // rax

PVOID v1; // rdi

__int64 v2; // rax

ULONG *buf_2; // rax

ULONG *v4; // rsi

void *v5; // rbx

PVOID result; // rax

struct _RTL_BITMAP BitMapHeader; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-28h] BYREF

struct _RTL_BITMAP v8; // [rsp+30h] [rbp-18h] BYREF

buf_1 = ExAllocatePoolWithTag(NonPagedPool, 0x20, "VHLF"); // [1]

v1 = buf_1;

if (buf_1) {

memset(buf_1, 0, 0x20);

v2 = sub_14000B82C(); // [2]

*(v1 + 1) = v2; // [3]

if (v2) {

buf_2 = ExAllocatePoolWithTag(NonPagedPool, 0x2000, "VHLF"); // [4]

v4 = buf_2;

if (buf_2) {

v5 = buf_2 + 0x400;

memset(buf_2, 0, 0x1000);

memset(v5, 0, 0x1000);

*&BitMapHeader.SizeOfBitMap = 0;

BitMapHeader.Buffer = 0;

RtlInitializeBitMap(&BitMapHeader, v4, 0x8000); // [5]

*&v8.SizeOfBitMap = 0;

v8.Buffer = 0;

RtlInitializeBitMap(&v8, v5, 0x8000); // [6]

result = v1;

*(v1 + 2) = v4; // [7]

*(v1 + 3) = v5; // [8]

return result;

}

ExFreePoolWithTag(*(v1 + 1), "VHLF");

}

ExFreePoolWithTag(v1, "VHLF");

}

return NULL;

}

At [1], the function allocates a 0x20-byte buffer from NonPagedPool using ExAllocatePoolWithTag with the tag VHLF. This buffer will serve as the main structure returned by the function. At [2], the function proceeds by calling sub_14000B82C:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

PVOID sub_14000B82C() {

PVOID PoolWithTag; // rax

char *v1; // rdi

unsigned int msr_idx; // ebx

struct _RTL_BITMAP BitMapHeader; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-38h] BYREF

struct _RTL_BITMAP v4; // [rsp+30h] [rbp-28h] BYREF

PoolWithTag = ExAllocatePoolWithTag(NonPagedPool, 0x1000, "VHLF"); // [1]

v1 = PoolWithTag;

msr_idx = 0;

if (PoolWithTag) {

memset(PoolWithTag, 0, 0x1000);

memset(v1, 0xFF, 0x400); // [2]

memset(v1 + 0x400, 0xFF, 0x400); // [3]

*&BitMapHeader.SizeOfBitMap = 0;

BitMapHeader.Buffer = 0;

RtlInitializeBitMap(&BitMapHeader, v1, 0x2000); // [3]

RtlClearBits(&BitMapHeader, IA32_MPERF, 2); // [4]

while (msr_idx < 0x1000)

readmsr(msr_idx++);

*&v4.SizeOfBitMap = 0;

v4.Buffer = 0;

RtlInitializeBitMap(&v4, v1 + 0x100, 0x2000); // [5]

RtlClearBits(&v4, IA32_TSC, 2); // [6]

return v1; // [7]

}

return PoolWithTag;

}

At [1], the function allocates a 0x1000-byte buffer from NonPagedPool using ExAllocatePoolWithTag with the tag VHLF. At [2] and [3], it initializes the first 0x800-byte of the buffer with 0xFF, effectively setting all bits to 1 in the first half of the allocated memory. At [3], it initializes a bitmap structure using RtlInitializeBitMap with the entire allocated buffer, creating an 0x2000 bit bitmap. At [4], it clears 2 bits in the bitmap starting at the position of IA32_MPERF using RtlClearBits.

Next, At [5], it initializes another bitmap structure (v4) using the second quarter of the allocated buffer (v1 + 0x100), again creating an 0x2000 bit bitmap. At [6], it clears 2 bits in the second bitmap starting at the position of IA32_TSC using RtlClearBits. Lastly, at [7], it returns a pointer to the allocated buffer.

Let’s take a small break, and talk about the MSR-Bitmap Address.

- MSRs and Virtualization: Model Specific Registers (MSRs) are special registers in x86 processors that control various CPU features and behaviors. In a virtualized environment, guest operating systems may attempt to read from or write to these MSRs.

- The Challenge: Without special handling, every MSR access by a guest OS would cause a VM exit (transfer control from the guest to the hypervisor). This is because the hypervisor needs to ensure that the guest doesn’t access or modify MSRs in a way that could compromise the system’s security or stability.

- Performance Impact: If every MSR access caused a VM exit, it would significantly degrade performance, as VM exits are relatively expensive operations in terms of CPU cycles.

- The Solution - MSR-Bitmap: The MSR-Bitmap is a feature provided by Intel’s VMX technology to address this issue. It allows the hypervisor to specify which MSR accesses should cause VM exits and which should be allowed to proceed without hypervisor intervention.

-

How it Works:

- The MSR-Bitmap is a

4 KBmemory area where each bit corresponds to a specific MSR. - If a bit is set (

1), access to the corresponding MSR causes a VM exit. - If a bit is clear (

0), the processor allows the access without a VM exit.

- The MSR-Bitmap is a

-

Selective Control: This mechanism allows the hypervisor to:

- Trap accesses to sensitive MSRs that require hypervisor intervention.

- Allow direct access to non-sensitive MSRs, improving performance by avoiding unnecessary VM exits.

The use of RtlClearBits for specific MSRs (like IA32_MPERF and IA32_TSC) suggests that the code is setting up the bitmap to allow direct access to these particular MSRs without causing VM exits. IA32_MPERF and IA32_TSC are both MSRs used in x86 architecture CPUs for performance monitoring and timing. For more information, you can refer to the details in the Intel SDM.

Back now to sub_14000BAC4, At [3], it stores the pointer to the MSR bitmap structure in the second 8-byte chunk of the main buffer (buf_1). At [4] the function allocates an additional 0x2000-byte buffer (8 KB) from the NonPagedPool. At [5], it initializes a bitmap structure using RtlInitializeBitMap with the first half (4 KB) of the buffer allocated in step [4]. Next, at [6], another bitmap structure is initialized, this time using the second half (4 KB) of the buffer from step [4].

At [7] and [8], the function stores pointers to the two bitmap buffers in the third and fourth qword fields of the main buffer (buf_1) allocated in step [1].

Finally, at [9], the function returns a pointer to the main buffer, now populated with:

- At offset

8: A pointer to the MSR bitmap structure. - At offset

16(0x10) : A pointer to the first bitmap buffer. - At offset

24(0x18) : A pointer to the second bitmap buffer.

I suspect that the final two bitmaps will later serve as the I/O-Bitmap.

Similar to how the MSR bitmap controls which MSRs cause a VM exit, the I/O bitmap similarly controls access to I/O ports, enabling the hypervisor to manage and intercept I/O operations performed by the guest operating systems.

Since I/O bitmaps were mentioned, let’s explain them now:

-

Purpose: The I/O bitmap is used to control VM exits for I/O instructions (

IN,OUT,INS,OUTS) executed by the guest. -

Structure: The I/O bitmap consists of two 4 KB pages:

- First page covers ports

0x0000to0x7FFF. - Second page covers ports

0x8000to0xFFFF.

- First page covers ports

-

Functionality:

- When a bit is set (

1), access to the corresponding I/O port triggers a VM exit. - When a bit is clear (

0), the I/O access proceeds without causing a VM exit.

- When a bit is set (

- VMCS Fields: The physical addresses of these two pages are stored in the VMCS (which we will discuss in greater detail later).

I/O operations can trigger a VM exit, offering opportunities for interesting interactions on the hypervisor’s side as it handles these events. Spoiler: The ‘HVM’ challenge from Flare-On’s 2023 leverages this mechanism.

Now, let’s return to analyzing the functions sub_14000BDE0 ([9]), sub_14000C614 ([13]), and sub_14000C638 ([14]), which are invoked by sub_14000B624 (run_function_on_all_logical_processors).

sub_14000BDE0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

NTSTATUS __stdcall sub_14000BDE0() {

unsigned __int64 v0; // rax

__int64 v2; // [rsp+38h] [rbp+10h]

v0 = readmsr(IA32_FEATURE_CONTROL); // [1]

HIDWORD(v2) = HIDWORD(v0);

if ((v0 & 1) != 0) // [2]

return STATUS_SUCCESS;

LODWORD(v2) = v0 | 1; // [3]

sub_140002FD8(0x3A, v2); // [4]

return (readmsr(IA32_FEATURE_CONTROL) & 1) == 0 ? STATUS_DEVICE_CONFIGURATION_ERROR: STATUS_SUCCESS; // [5]

}

At [1], we encounter a second instance of reading the IA32_FEATURE_CONTROL MSR using readmsr. Next, at [2], the code checks the lock bit (bit 0), and if it is set, the function returns STATUS_SUCCESS. Otherwise, at [3], the lock bit is set and sub_140002FD8 is called:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

.text:0000000140002FD8 ; unsigned __int64 __fastcall sub_140002FD8(unsigned int, unsigned __int64)

.text:0000000140002FD8 sub_140002FD8 proc near ; CODE XREF: sub_14000BDE0+2C↓p

.text:0000000140002FD8 48 8B C2 mov rax, rdx

.text:0000000140002FDB 48 C1 EA 20 shr rdx, 20h

.text:0000000140002FDF 0F 30 wrmsr

.text:0000000140002FE1 C3 retn

.text:0000000140002FE1 sub_140002FD8 endp

Similar to the RDMSR instruction for reading from an MSR, there is also a WRMSR instruction for writing to an MSR. We can rename sub_140002FD8 to writemsr. In summary, the function sub_14000BDE0 ensures that the lock bit of the IA32_FEATURE_CONTROL MSR is set; if it isn’t, the function attempts to set it. As mentioned in the section on Enabling and Entering VMX Operation, this is a necessary step before executing a VMXON instruction:

To enable VMX support in a platform, BIOS must set bit 1, bit 2, or both (see below), as well as the lock bit.

We’re now left with sub_14000C614 ([13]) and sub_14000C638 ([14]). sub_14000C614 executes first, while sub_14000C638 runs only if sub_14000C614 fails. sub_14000C638 appears to be a clean-up function, so we can omit it to keep this post brief.

sub_14000C614

sub_14000C614 is invoked by sub_14000B624 (run_function_on_all_logical_processors), with the return value from sub_14000BAC4 passed as an argument. As you recall, sub_14000BAC4 allocated a buffer of 0x20-byte and then set its contents to:

- At offset

8: Pointer to the MSR bitmap structure. - At offset

0x10: Pointer to the first bitmap buffer. - At offset

0x18: Pointer to the second bitmap buffer.

To improve the readability of the decompiled code, we can define a custom structure in IDA with the following layout:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

00000000 flhv_bitmap struc ; (sizeof=0x20, mappedto_33)

00000000 unk dq ?

00000008 msr_bitmap dq ?

00000010 another_bitmap_1 dq ?

00000018 another_bitmap_2 dq ?

00000020 flhv_bitmap ends

00000020

sub_14000C614:

1

2

3

NTSTATUS __fastcall sub_14000C614(__int64 a1) {

return sub_140001320(sub_14000BBCC, a1) == STATUS_SUCCESS ? STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL: STATUS_SUCCESS;

}

sub_14000C614 calls sub_140001320 with two arguments: a function pointer - sub_14000BBCC, and its first argument (a1). It then inverts the success/failure status of the result. If the called function succeeds (returns STATUS_SUCCESS), sub_14000C614 returns STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL, and vice versa.

sub_140001320:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

.text:0000000140001320 ; __int64 __fastcall sub_140001320(void (__fastcall *)(_QWORD *, char *, __int64), __int64)

.text:0000000140001320 sub_140001320 proc near ; CODE XREF: sub_14000C614+E↓p

.text:0000000140001320 9C pushfq ; [1]

.text:0000000140001321 50 push rax

.text:0000000140001322 51 push rcx

.text:0000000140001323 52 push rdx

.text:0000000140001324 53 push rbx

.text:0000000140001325 6A FF push 0FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFh

.text:0000000140001327 55 push rbp

.text:0000000140001328 56 push rsi

.text:0000000140001329 57 push rdi

.text:000000014000132A 41 50 push r8

.text:000000014000132C 41 51 push r9

.text:000000014000132E 41 52 push r10

.text:0000000140001330 41 53 push r11

.text:0000000140001332 41 54 push r12

.text:0000000140001334 41 55 push r13

.text:0000000140001336 41 56 push r14

.text:0000000140001338 41 57 push r15 ; [2]

.text:000000014000133A 48 8B C1 mov rax, rcx ; [3]

.text:000000014000133D 4C 8B C2 mov r8, rdx ; [4]

.text:0000000140001340 48 BA 77 13 00 40 01 00 mov rdx, offset byte_140001377 ; [5]

.text:000000014000134A 48 8B CC mov rcx, rsp ; [6]

.text:000000014000134D 48 83 EC 20 sub rsp, 20h

.text:0000000140001351 FF D0 call rax ; [7]

.text:0000000140001353 48 83 C4 20 add rsp, 20h

.text:0000000140001357 41 5F pop r15 ; [8]

.text:0000000140001359 41 5E pop r14

.text:000000014000135B 41 5D pop r13

.text:000000014000135D 41 5C pop r12

.text:000000014000135F 41 5B pop r11

.text:0000000140001361 41 5A pop r10

.text:0000000140001363 41 59 pop r9

.text:0000000140001365 41 58 pop r8

.text:0000000140001367 5F pop rdi

.text:0000000140001368 5E pop rsi

.text:0000000140001369 5D pop rbp

.text:000000014000136A 48 83 C4 08 add rsp, 8

.text:000000014000136E 5B pop rbx

.text:000000014000136F 5A pop rdx

.text:0000000140001370 59 pop rcx

.text:0000000140001371 58 pop rax

.text:0000000140001372 9D popfq ; [9]

.text:0000000140001373 48 33 C0 xor rax, rax

.text:0000000140001376 C3 retn

.text:0000000140001376 sub_140001320 endp

Between [1] and [2], the current general-purpose registers (GPRs). At [3], RAX is set to the first argument (sub_14000BBCC), and the function is invoked at [7]. At [6], the saved GPRs are passed as the first argument to sub_14000BBCC. At [5], byte_140001377 is passed as the second argument, while the third argument points to the flhv_bitmap structure. Once sub_14000BBCC completes, the saved GPRs are restored between [8] and [9].

The function prototype for sub_14000BBCC is as follows:

1

void __fastcall sub_14000BBCC(_QWORD *saved_state, char *unk_140001377, flhv_bitmap *fhv_bitmaps);

Why is saving the current processor state necessary? It allows us to revert to a stable operating state if something goes wrong during the VMX initialization process.

sub_14000BBCC

Things are about to get really interesting—if you’re feeling a bit tired, take a moment to grab a coffee and stay focused. Considering the multiple actions within sub_14000BAC4, we will break it down into smaller sections for better clarity.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

void __fastcall sub_14000BBCC(_QWORD *saved_state, char *unk_140001377, flhv_bitmap *fhv_bitmaps) {

PVOID PoolWithTag; // rax

_QWORD *v7; // rdi

__int64 v8; // rax

PVOID v9; // rax

PVOID v10; // rax

PVOID v11; // rax

__int64 v12; // rax

__int64 v13; // r14

unsigned __int64 v14; // rbx

unsigned __int64 v15; // rax

unsigned __int64 v16; // rcx

unsigned __int64 v17; // rbx

unsigned __int64 v18; // rax

unsigned __int64 v19; // rcx

char v20; // cf

char v21; // zf

PHYSICAL_ADDRESS PhysicalAddress; // [rsp+58h] [rbp+20h]

if (fhv_bitmaps) {

PoolWithTag = ExAllocatePoolWithTag(NonPagedPool, 0x28, "VHLF"); // [1]

v7 = PoolWithTag;

if (PoolWithTag) {

memset(PoolWithTag, 0, 0x28);

*v7 = fhv_bitmaps; // [2]

_InterlockedIncrement(fhv_bitmaps); // [3]

v8 = sub_14000B0DC(); // [4]

v7[4] = v8; // [5]

if (v8) {

v9 = sub_140002CDC(0x6000); // [6]

v7[1] = v9; // [7]

if (v9) {

memset(v9, 0, 0x6000);

v10 = ExAllocatePoolWithTag(NonPagedPool, 0x1000, "VHLF"); // [8]

v7 [3] = v10; // [9]

if (v10) {

memset(v10, 0, 0x1000);

v11 = ExAllocatePoolWithTag(NonPagedPool, 0x1000, "VHLF"); // [10]

v7[2] = v11; // [11]

if (v11) {

memset(v11, 0, 0x1000);

v12 = v7[1]; // [12]

v13 = v12 + 0x5FF0;

*(v12 + 0x5FF0) = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF;

*(v12 + 0x5FF8) = v7; // [13]

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

}

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

}

}

}

}

}

}

At [1], a 0x28-byte buffer (v7) is allocated. Following that, at [2], the buffer’s first qword (offset 0) is assigned to the fhv_bitmaps structure (which passed to sub_14000BBCC). Subsequently, at [3], the first dword within the fhv_bitmaps structure is atomically incremented, likely to synchronize access to this structure. At [4], the function sub_14000B0DC initializes the EPT. Next, at [5], the EPT-related structure (v8) is stored at offset 0x20 in the v7 buffer. Then, at [6], the function sub_140002CDC allocates a contiguous 0x6000-byte buffer (v9) in physical memory using MmAllocateContiguousMemory. At [7], this buffer (v9) is stored in the v7 buffer at offset 8.

At [8] and [10], 0x1000-byte buffers (v10 and v11) are allocated. At [9] and [11], these buffers are stored in the v7 buffer at offsets 0x18 and 0x10, respectively. Next, at [12], the contiguous buffer (v9) is referenced, and unclear values are assigned at unspecified offsets until [13].

The layout of the v7 buffer (referred to as fhv_ctx from now on) is as follows:

-

At offset

0: A pointer to thefhv_bitmapsstructure. -

At offset

8: A pointer to a contiguous0x6000-byte buffer (v9). -

At offset

0x10: A pointer to the first 0x1000-byte buffer (v10). -

At offset

0x18: A pointer to the second 0x1000-byte buffer (v11). -

At offset

0x20: A pointer to the EPT data structures.

We proceed to the next part of the code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

void __fastcall sub_14000BBCC(_QWORD *saved_state, char *unk_140001377, flhv_bitmap *fhv_bitmaps) {

unsigned __int64 cr0_fixed0; // rbx

unsigned __int64 cr0_fixed1; // rax

unsigned __int64 cr0; // rcx

unsigned __int64 cr4_fixed0; // rbx

unsigned __int64 cr4_fixed1; // rax

unsigned __int64 cr4; // rcx

char v20; // cf

char v21; // zf

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

cr0_fixed0 = readmsr(IA32_VMX_CR0_FIXED0); // [1]

cr0_fixed1 = readmsr(IA32_VMX_CR0_FIXED1); // [2]

cr0 = __readcr0(); // [3]

__writecr0(cr0_fixed0 | cr0_fixed1 & cr0); // [4]

cr4_fixed0 = readmsr(IA32_VMX_CR4_FIXED0); // [5]

cr4_fixed1 = readmsr(IA32_VMX_CR4_FIXED1); // [6]

cr4 = __readcr4(); // [7]

__writecr4(cr4_fixed0 | cr4_fixed1 & cr4); // [8]

*fhv_ctx->buf_0x1000_1 = readmsr(IA32_VMX_BASIC) & 0x7FFFFFFF; // [9]

PhysicalAddress = MmGetPhysicalAddress(fhv_ctx->buf_0x1000_1); // [10]

__asm { vmxon [rsp+0x38+PhysicalAddress] } // [11]

if (!(v20 | v21)) { // [12]

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

}

}

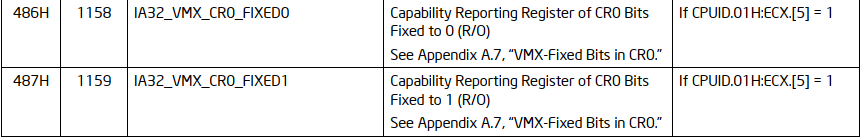

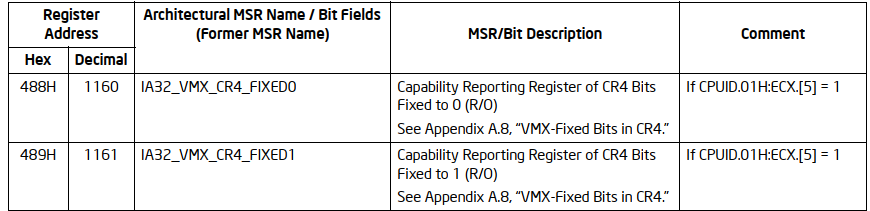

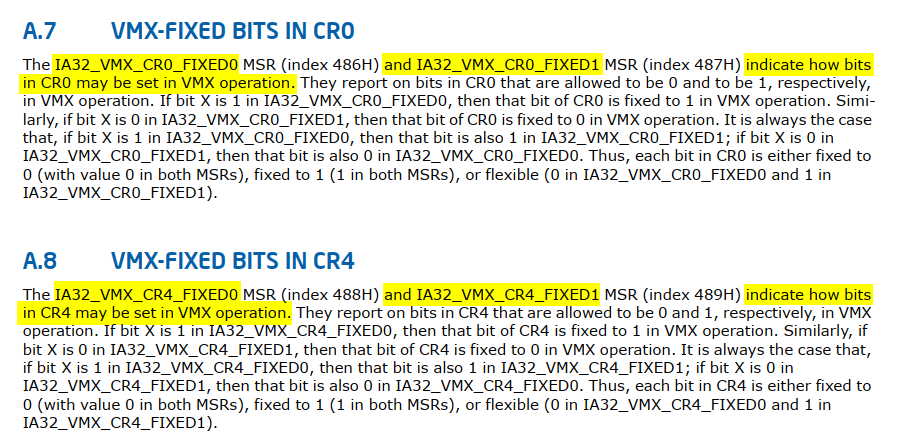

At [1], [2], [5] and [6], the MSRs IA32_VMX_CR0_FIXED0 (0x486), IA32_VMX_CR0_FIXED1 (0x487), IA32_VMX_CR4_FIXED0 (0x488) and IA32_VMX_CR4_FIXED1 (0x489) are read.

What are these values, and why are they necessary?

First, as noted in the section on Enabling and Entering VMX Operation, there is a reference to CR4:

ENABLING AND ENTERING VMX OPERATION

Before system software can enter VMX operation, it enables VMX by setting CR4.VMXE[bit 13] = 1. VMX operation is then entered by executing the VMXON instruction. VMXON causes an invalid-opcode exception (#UD) if executed with CR4.VMXE = 0. Once in VMX operation, it is not possible to clear CR4.VMXE (see Section 24.8). System software leaves VMX operation by executing the VMXOFF instruction. CR4.VMXE can be cleared outside of VMX operation after executing of VMXOFF.

Additionally, in the chapter Introduction to Virtual Machine Extensions there is a section called Restrictions On VMX Operation:

RESTRICTIONS ON VMX OPERATION

VMX operation places restrictions on processor operation. These are detailed below:

- In VMX operation, processors may fix certain bits in CR0 and CR4 to specific values and not support other values. [… omitted for brevity …] Software should consult the VMX capability MSRs IA32_VMX_CR0_FIXED0 and IA32_VMX_CR0_FIXED1 to determine how bits in CR0 are fixed (see Appendix A.7). For CR4, software should consult the VMX capability MSRs IA32_VMX_CR4_FIXED0 and IA32_VMX_CR4_FIXED1 (see Appendix A.8).

NOTES:

The first processors to support VMX operation require that the following bits be 1 in VMX operation: CR0.PE, CR0.NE, CR0.PG, and CR4.VMXE. The restrictions on CR0.PE and CR0.PG imply that VMX operation is supported only in paged protected mode (including IA-32e mode). Therefore, guest software cannot be run in unpaged protected mode or in real-address mode. Later processors support a VM-execution control called “unrestricted guest” (see Section 25.6.2). If this control is 1, CR0.PE and CR0.PG may be 0 in VMX non-root operation (even if the capability MSR IA32_VMX_CR0_FIXED0 reports otherwise). Such processors allow guest software to run in unpaged protected mode or in real-address mode.

IA32_VMX_CR0_FIXED0, IA32_VMX_CR0_FIXED1, IA32_VMX_CR4_FIXED0 and IA32_VMX_CR4_FIXED1:

At [3], [7], [4], and [8], the current values of CR0 and CR4 are read and then modified according to the fixed values from the MSRs. We’re just about to enter and start running in VMX mode!

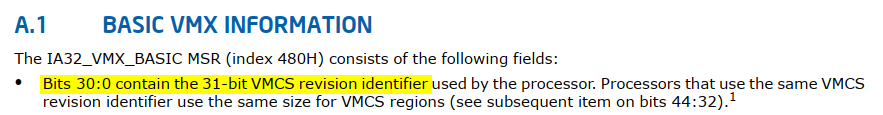

At [9], the IA32_VMX_BASIC MSR is read, with the lower 31 bits extracted and stored at offset 0 in buf_0x1000_1:

Why is this step ([9]) necessary? The chapter Virtual Machine Control Structures, covers this in the section titled Software Use of VMCS and Related Structures, specifically in the sub-section VMXON Region.

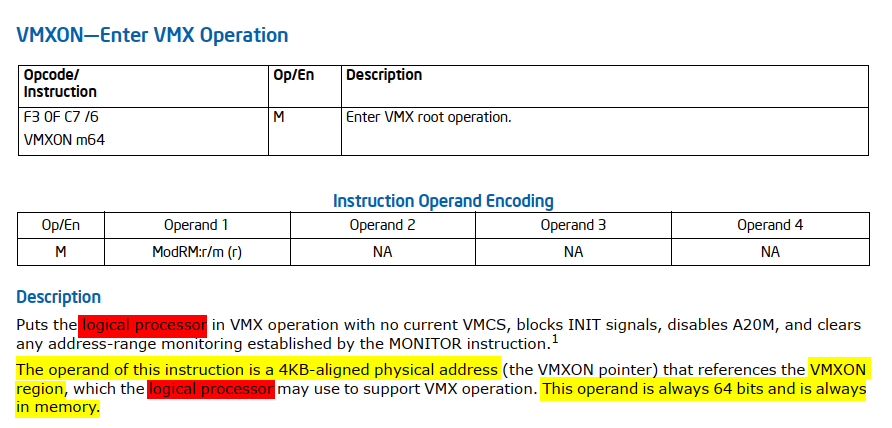

VMXON Region

Before executing VMXON, software allocates a region of memory (called the VMXON region)[1] that the logical processor uses to support VMX operation. The physical address of this region (the VMXON pointer) is provided in an operand to VMXON. The VMXON pointer is subject to the limitations that apply to VMCS pointers:

- The VMXON pointer must be 4-KByte aligned (bits 11:0 must be zero).

- The VMXON pointer must not set any bits beyond the processor’s physical-address width.

Before executing VMXON, software should write the VMCS revision identifier (see Section 25.2) to the VMXON region. (Specifically, it should write the 31-bit VMCS revision identifier to bits 30:0 of the first 4-byte of the VMXON region; bit 31 should be cleared to 0.) It need not initialize the VMXON region in any other way. Software should use a separate region for each logical processor and should not access or modify the VMXON region of a logical processor between execution of VMXON and VMXOFF on that logical processor. Doing otherwise may lead to unpredictable behavior (including behaviors identified in Section 25.11.1).

[1] - The amount of memory required for the VMXON region is the same as that required for a VMCS region. This size is implementation specific and can be determined by consulting the VMX capability MSR IA32_VMX_BASIC (see Appendix A.1).

Next, at [10], the physical address of buf_0x1000_1 is obtained, and at [11], it is used as the operand for the VMXON instruction.

VMXON

Do you recall the question: “Why is it necessary to run a specific function on all processors rather than just one?” Here is the answer: Since the

VMXONinstruction only causes the current logical processor to enter into VMX root operation, we need to apply it to the remaining logical processors.

See also: Two CPU in two modes - VMX and non-VMX modes

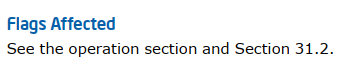

We can rename buf_0x1000_1 to vmxon_region. Lastly, at [12], the success of the VMXON instruction is verified by ensuring that both the ZF and CF flags are clear:

Moving forward, let’s examine the next portion of the code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

void __fastcall sub_14000BBCC(_QWORD *saved_state, char *unk_140001377, flhv_bitmap *fhv_bitmaps) {

char v20; // cf

char v21; // zf

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

sub_140002D30(); // [1]

sub_140002D70(); // [2]

*fhv_ctx->buf_0x1000_2 = readmsr(IA32_VMX_BASIC) & 0x7FFFFFFF; // [3]

MmGetPhysicalAddress_2 = MmGetPhysicalAddress(fhv_ctx->buf_0x1000_2); // [4]

__asm { vmclear [rsp+0x38+MmGetPhysicalAddress_2] } // [5]

if (!(v20 | v21)) { // [6]

__asm { vmptrld [rsp+0x38+MmGetPhysicalAddress_2] } // [7]

if (!(v20 + v20 + v21)) { // [8]

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

}

}

}

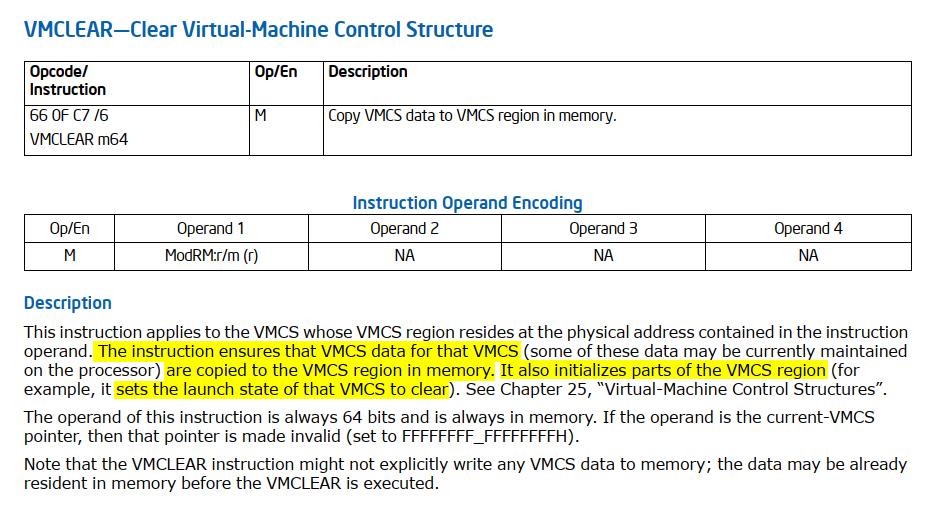

At [1] and [2], sub_140002D30 and sub_140002D70 execute the INVEPT and INVVPID instructions, which are beyond the scope of this post and will not be covered. Next, steps [3] and [4] replicate the earlier initialization of the VMXON region initialization, but this time using buf_0x1000_2. Then, at [5], the VMCLEAR instruction is executed.

VMCLEAR

VMCLEAR is typically executed before using a VMCS for a new virtual machine or when switching between VMCSs. At [6] the success of the VMCLEAR instruction is verified. We can rename buf_0x1000_2 to vmcs_region.

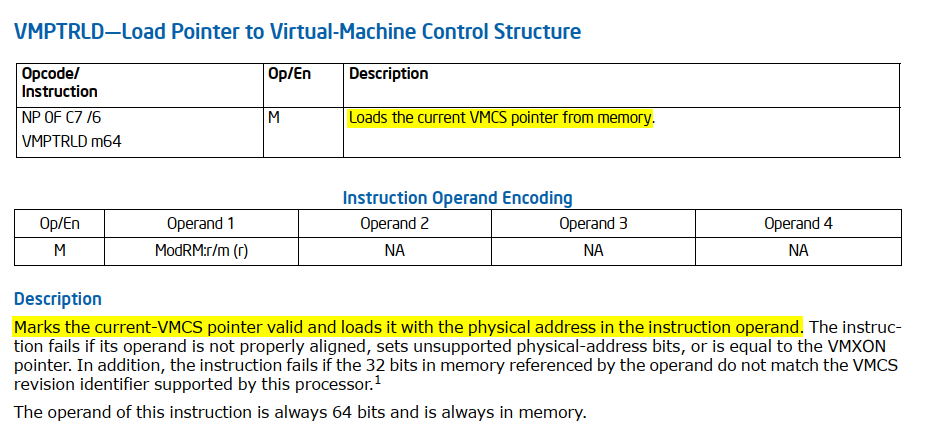

Next, at [7] the VMPTRLD instruction is executed.

VMPTRLD

VMPTRLD’s key purpose is to set the current VMCS. This is crucial because most VMX instructions operate on the current VMCS. By executing VMPTRLD, you’re essentially telling the processor which VMCS to use for subsequent VMX operations. At [8] the success of the VMPTRLD instruction is verified. In the next section, we’ll explore how the VMCS is initialized.

Next, sub_14000BBCC invokes sub_14000BE30:

1

if ( sub_14000BE30(fhv_ctx, saved_state, unk_140001377, v13) )

sub_14000BE30

The function sub_14000BE30 handles the initialization of the VMCS and performs several important tasks. In this section, we’ll focus on the most interesting aspects of its behavior.

One of the most frequently called functions is sub_140002FCC, which takes two arguments:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

char __fastcall sub_140002FCC(__int64 _RCX, __int64 _RDX) {

char v2; // cf

char v3; // zf

__asm { vmwrite rcx, rdx }

return v2 + v2 + v3;

}

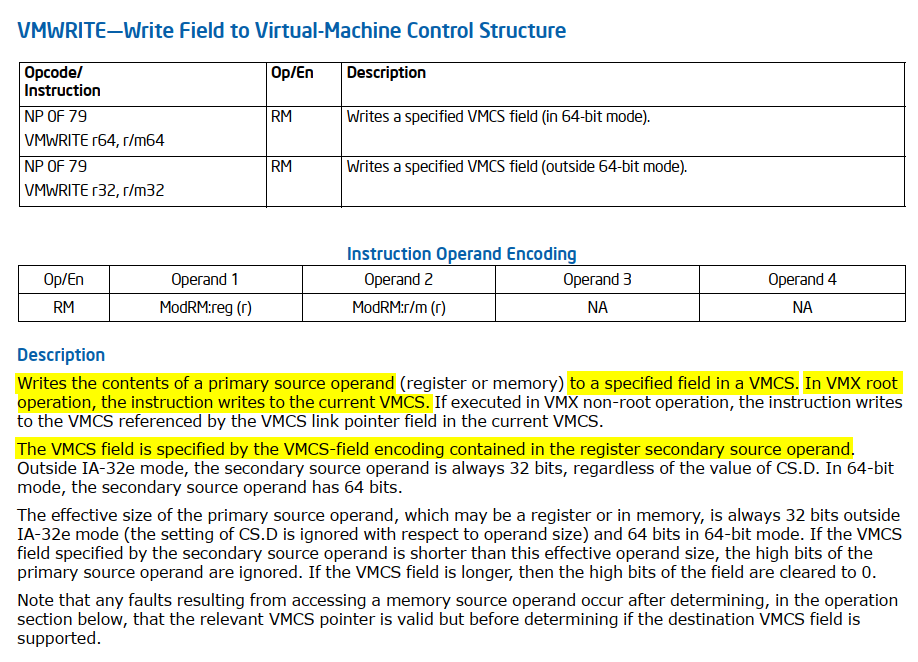

VMWRITE

To initialize the VMCS fields, Intel provides the VMWRITE instruction rather than directly writing to memory. This approach simplifies managing the VMCS fields and ensures that the values are correctly written to the appropriate locations in the VMCS structure. The VMCS fields are encoded to uniquely identify different elements within the VMCS. Each field is assigned a specific encoding value, which the VMWRITE and VMREAD instructions use to write or read the corresponding fields.

We can rename sub_140002FCC to vmwrite_rcx_rdx for better clarity. Since it’s clear that this function takes an encoded VMCS field as a parameter, we can simplify future work by importing a header file with an enum of VMCS field values (you can use this one). Updating the type declaration for sub_140002FCC (vmwrite_rcx_rdx) will result in clearer decompiled code.

Next, let’s explore how the Guest-State Area VMCS fields are initialized:

For clarity, I’ve reorganized and refined some parts of the code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

char __fastcall sub_14000BE30(flhv_ctx *fhv_ctx, __int64 saved_state, __int64 unk_140001377, __int64 a4_v13) {

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

*&gdtr.limit = 0;

LOWORD(gdtr.base) = 0;

sgdt(&gdtr);

*&idtr.limit = 0;

LOWORD(idtr.base) = 0;

__sidt(&idtr);

es = get_es(); // [1]

cs = get_cs();

ss = get_ss();

ds = get_ds();

fs = get_fs();

gs = get_gs();

ldtr = sldt();

tr = str();

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_ES_SELECTOR, es);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_CS_SELECTOR, cs);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_SS_SELECTOR, ss);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_DS_SELECTOR, ds);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_FS_SELECTOR, fs);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_GS_SELECTOR, gs);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_LDTR_SELECTOR, ldtr);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_TR_SELECTOR, tr);

es__ = get_es(); // [2]

cs__ = get_cs();

ss__ = get_ss();

ds__ = get_ds();

fs__ = get_fs();

gs__ = get_gs();

ldtr__ = sldt();

tr__ = str();

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_ES_LIMIT, __segmentlimit(es__));

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_CS_LIMIT, __segmentlimit(cs__));

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_SS_LIMIT, __segmentlimit(ss__));

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_DS_LIMIT, __segmentlimit(ds__));

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_FS_LIMIT, __segmentlimit(fs__));

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_GS_LIMIT, __segmentlimit(gs__));

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_LDTR_LIMIT, __segmentlimit(ldtr__));

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_TR_LIMIT, __segmentlimit(tr__));

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_GDTR_LIMIT, gdtr.limit);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_IDTR_LIMIT, idtr.limit);

es___ = get_es(); // [3]

cs___ = get_cs();

ss___ = get_ss();

ds = get_ds();

fs___ = get_fs();

gs___ = get_gs();

ss_seg_ar = get_seg_ar(ss___);

es_seg_ar = get_seg_ar(es___);

cs_seg_ar = get_seg_ar(cs___);

ds_seg_ar = get_seg_ar(ds);

fs_seg_ar = get_seg_ar(fs___);

gs_seg_ar = get_seg_ar(gs___);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_ES_AR_BYTES, es_seg_ar);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_CS_AR_BYTES, cs_seg_ar);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_SS_AR_BYTES, ss_seg_ar);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_DS_AR_BYTES, seg_ar);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_FS_AR_BYTES, fs_seg_ar);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_GS_AR_BYTES, gs_seg_ar);

ldtr_ = sldt();

tr___ = str();

tr_ar = get_seg_ar(tr___);

ldtr_ar = get_seg_ar(ldtr_);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_LDTR_AR_BYTES, ldtr_ar);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_TR_AR_BYTES, tr_ar); // [4]

ia32_sysenter_cs = readmsr(IA32_SYSENTER_CS);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_SYSENTER_CS, ia32_sysenter_cs);

cr0_ = __readcr0();

cr3 = __readcr3();

cr4_ = __readcr4();

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_CR0, cr0_);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_CR3, cr3);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_CR4, cr4_);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_ES_BASE, 0);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_CS_BASE, 0);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_SS_BASE, 0);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_DS_BASE, 0);

ia32_fs_base = readmsr(IA32_FS_BASE);

ia32_gs_base = readmsr(IA32_GS_BASE);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_FS_BASE, ia32_fs_base);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_GS_BASE, ia32_gs_base);

ldtr___ = sldt();

tr____ = str();

v70 = sub_14000BA30(*(&gdtr + 2), ldtr___);

v72 = sub_14000BA30(*(&gdtr + 2), tr____);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_LDTR_BASE, v70);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_TR_BASE, v72);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_GDTR_BASE, *(&gdtr + 2));

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_IDTR_BASE, *(&idtr + 2));

dr7 = __readdr(7);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_DR7, dr7);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_RSP, saved_state); // [5]

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_RIP, unk_140001377); // [6]

eflags = __readeflags();

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_RFLAGS, eflags);

ia32_sysenter_esp = readmsr(IA32_SYSENTER_ESP);

ia32_sysenter_eip = readmsr(IA32_SYSENTER_EIP);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_SYSENTER_ESP, ia32_sysenter_esp);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_SYSENTER_EIP, ia32_sysenter_eip);

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

}

Between [1] and [2], the segment selectors are initialized; between [2] and [3], the segment limits are initialized; and between [3] and [4], the segment access rights are initialized. At [5], GUEST_RSP is set to saved_state (a2). Lastly, at [6], GUEST_RIP is set to unk_140001377 (a3), which we can rename to initial_guest_rip for clarity.

Next, let’s examine how the Host-State Area VMCS fields are initialized:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

char __fastcall sub_14000BE30(flhv_ctx *fhv_ctx, __int64 saved_state, __int64 initial_guest_rip, __int64 a4_v13) {

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

*&gdtr.limit = 0;

LOWORD(gdtr.base) = 0;

sgdt(&gdtr);

*&idtr.limit = 0;

LOWORD(idtr.base) = 0;

__sidt(&idtr);

es_ = get_es(); // [1]

cs_ = get_cs();

ss_ = get_ss();

ds_ = get_ds();

fs_ = get_fs();

gs_ = get_gs();

tr_ = str();

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_ES_SELECTOR, es_ & 0xF8);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_CS_SELECTOR, cs_ & 0xF8);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_SS_SELECTOR, ss_ & 0xF8);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_DS_SELECTOR, ds_ & 0xF8);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_FS_SELECTOR, fs_ & 0xF8);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_GS_SELECTOR, gs_ & 0xF8);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_TR_SELECTOR, tr_ & 0xF8); // [2]

ia32_sysenter_cs_ = readmsr(IA32_SYSENTER_CS);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_SYSENTER_CS, ia32_sysenter_cs_);

cr0__ = __readcr0();

cr3__ = __readcr3();

cr4__ = __readcr4();

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_CR0, cr0__);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_CR3, cr3__);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_CR4, cr4__);

ia32_fs_base_ = readmsr(IA32_FS_BASE);

ia32_gs_base_ = readmsr(IA32_GS_BASE);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_FS_BASE, ia32_fs_base_);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_GS_BASE, ia32_gs_base_);

tr_____ = str();

v83 = sub_14000BA30(*(&gdtr.limit + 1), tr_____);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_TR_BASE, v83);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_GDTR_BASE, *(&gdtr + 2));

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_IDTR_BASE, *(&idtr + 2));

ia32_sysenter_esp_ = readmsr(IA32_SYSENTER_ESP);

ia32_sysenter_eip_ = readmsr(IA32_SYSENTER_EIP);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_SYSENTER_ESP, ia32_sysenter_esp_);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_SYSENTER_EIP, ia32_sysenter_eip_);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_RSP, a4_v13); // [3]

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(HOST_RIP, sub_1400013E6); // [4]

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

}

Between [1] and [2], the segment selectors are initialized. At [3], HOST_RSP is set to a4_v13 (corresponding to v13 from sub_14000BBCC). For clarity, a4_v13 can be renamed to host_rip. Now, let’s revisit the snippet from sub_14000BBCC:

Next, at [12], the contiguous buffer (

v9) is referenced, and unclear values are assigned at various offsets until [13].

After allocating a buffer of 0x6000-byte, the top of the stack pointer (RSP, pointed by v13) is set to offset 0x5FF0 within this buffer. The offset 0x5FF8 is initialized to point to fhv_ctx (v7), while offset 0x5FF0 is set to 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF, which serves as a marker or sentinel value. This configuration positions the stack pointer at 0x5FF0, just above the fhv_ctx pointer at 0x5FF8, ensuring that the stack grows downwards from 0x5FF0 towards the start of the allocated buffer at 0x6000-byte, providing space for stack operations and preserving the sentinel value at the top of the stack.

Lastly, at [4], HOST_RIP is set to sub_1400013E6. This step is particularly interesting and will be discussed in depth later.

We continue with the remains VMCS fields to initialize:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

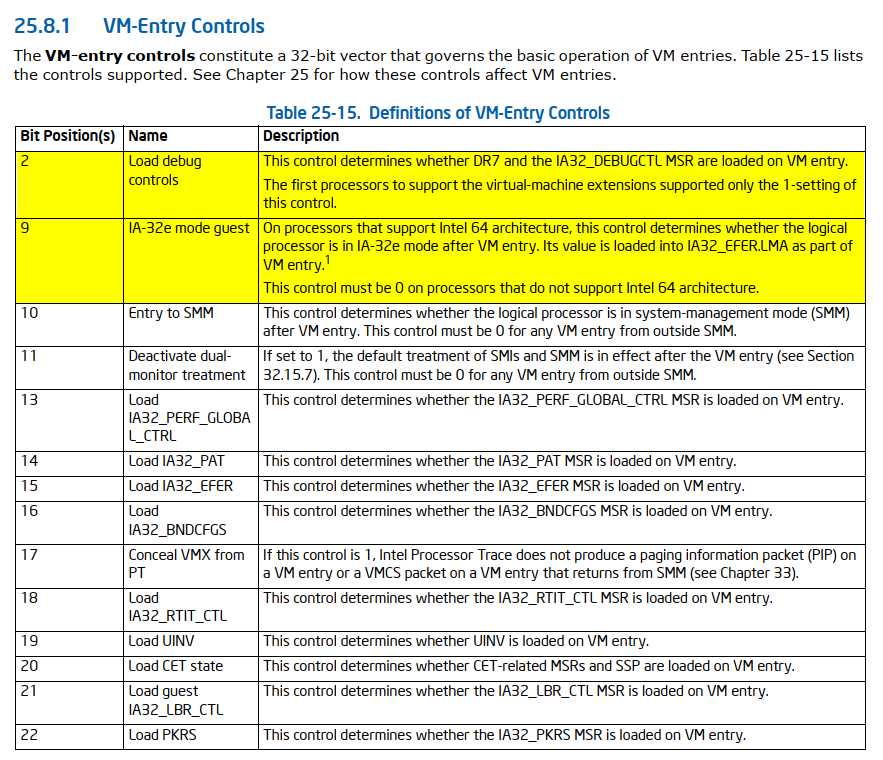

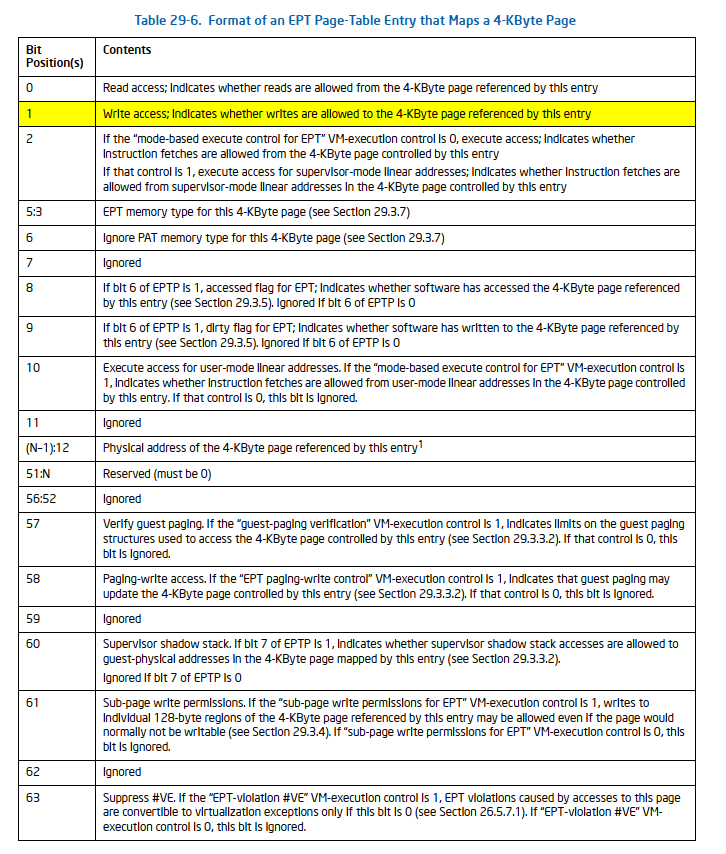

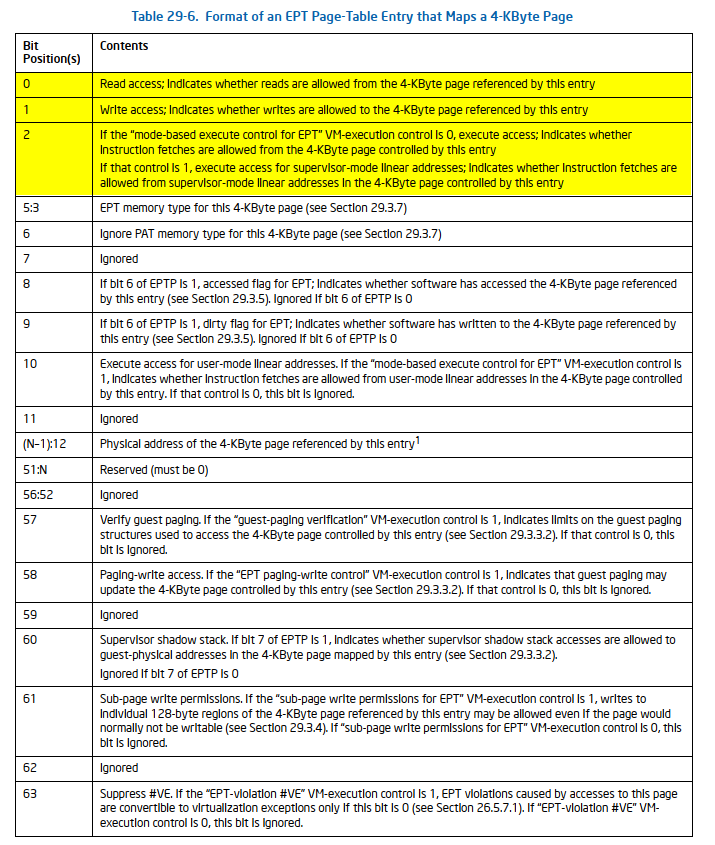

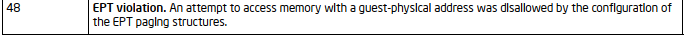

char __fastcall sub_14000BE30(flhv_ctx *fhv_ctx, __int64 saved_state, __int64 initial_guest_rip, __int64 host_rsp) {

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

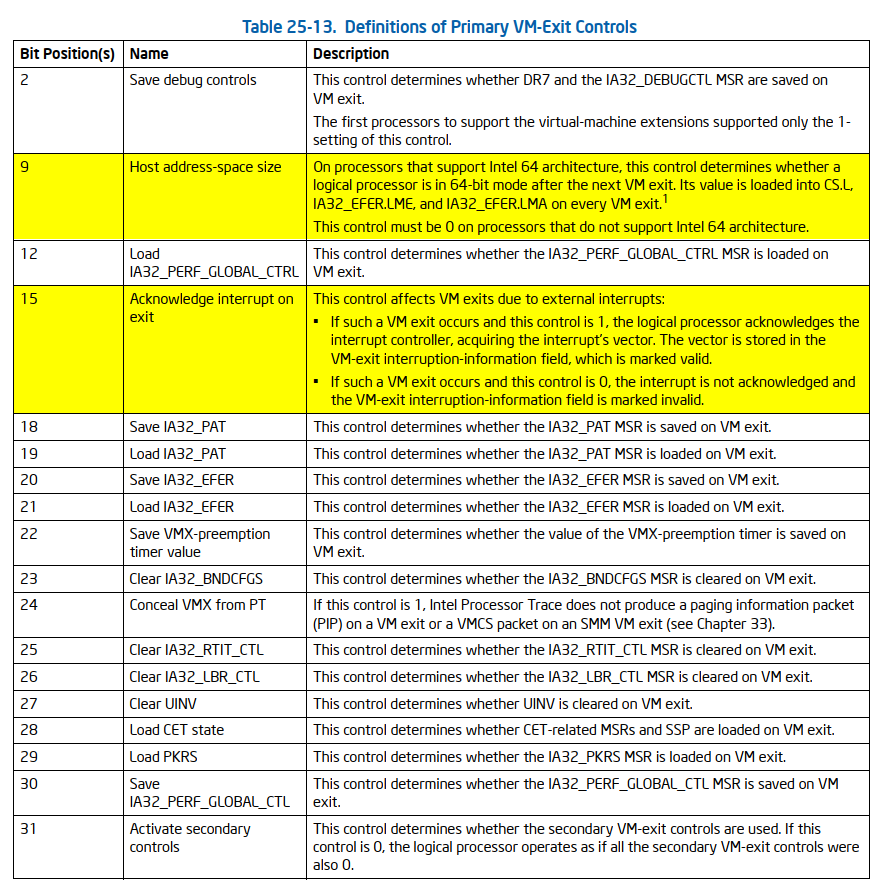

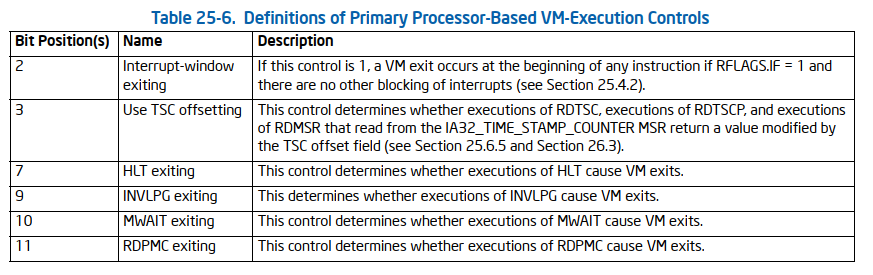

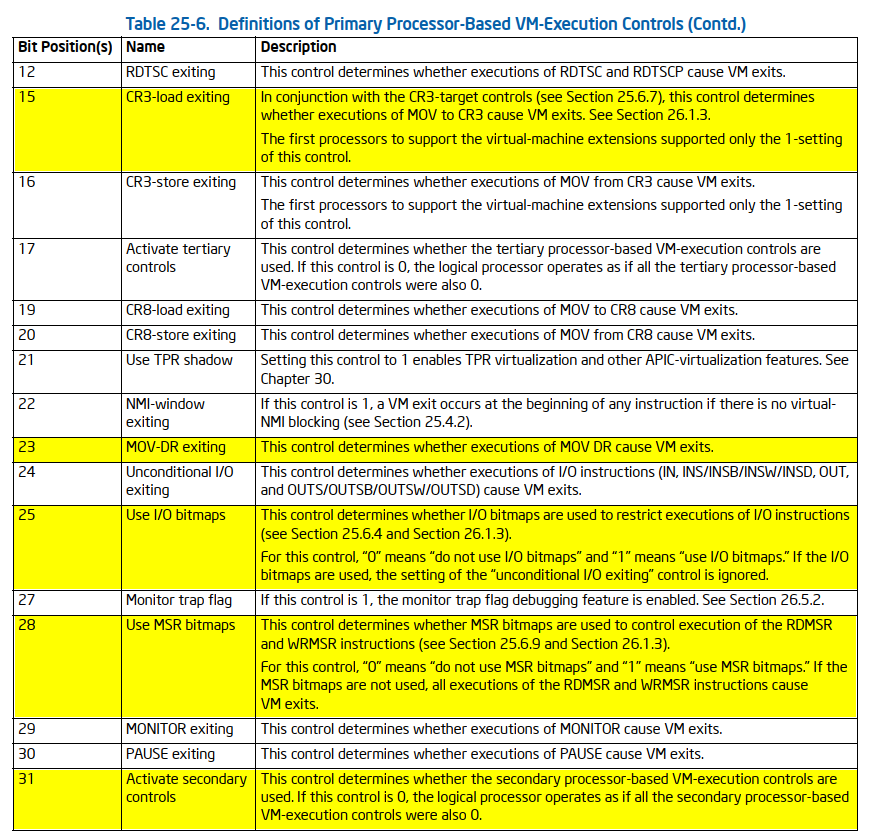

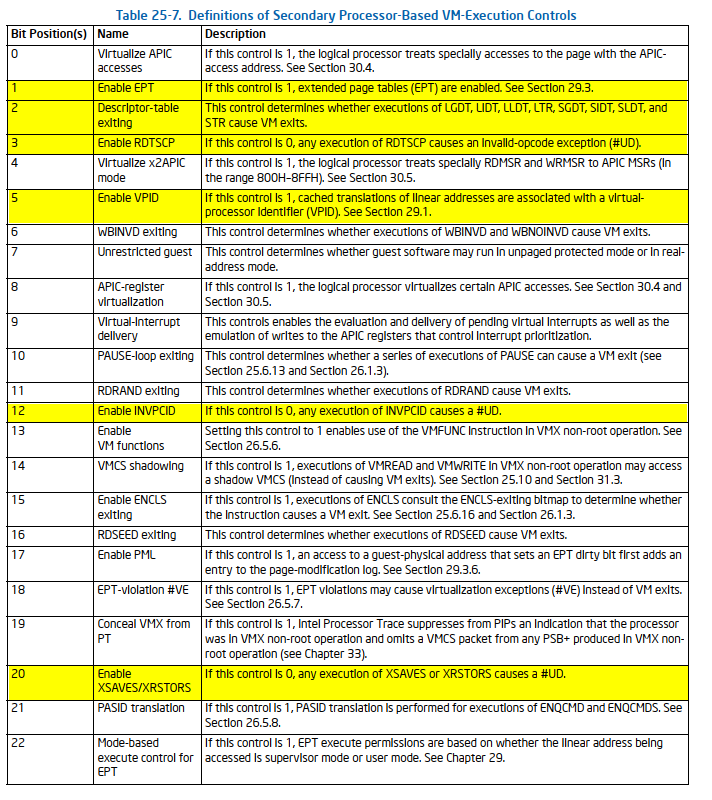

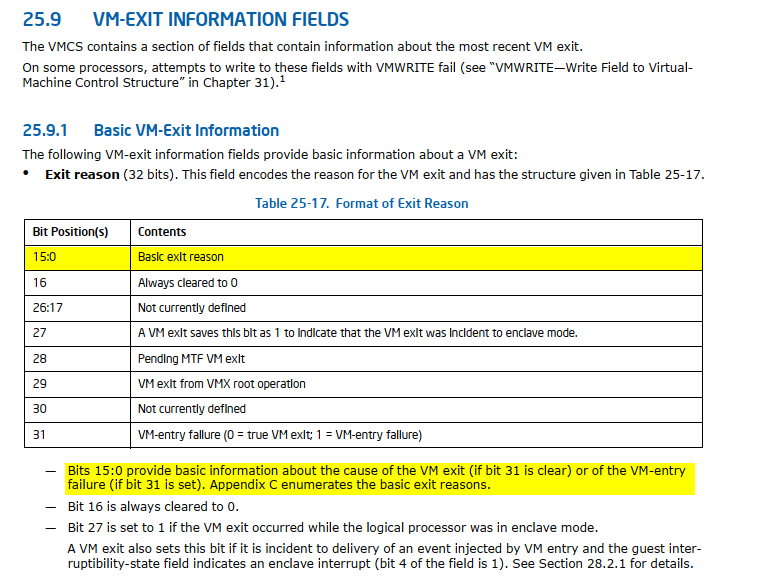

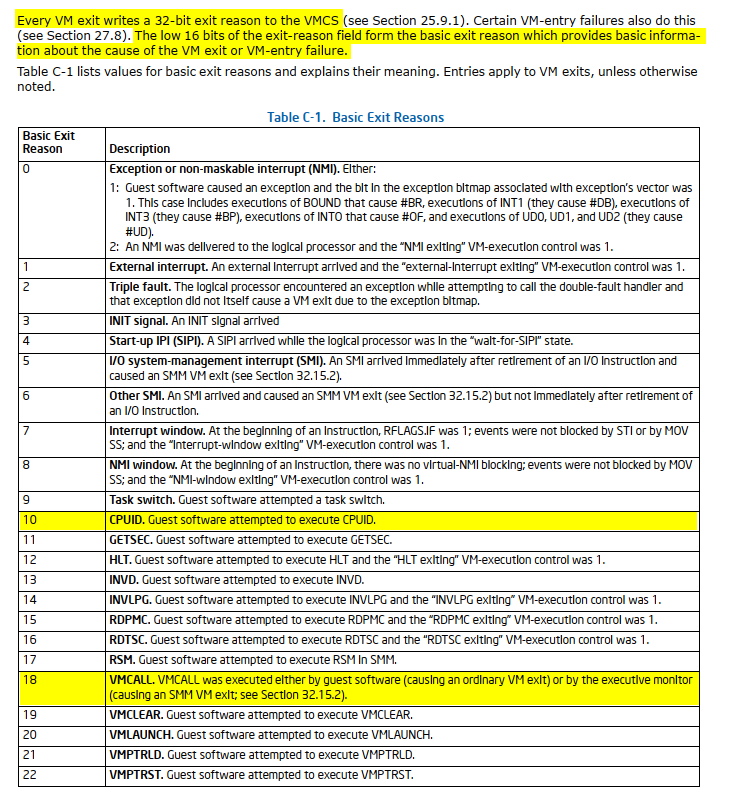

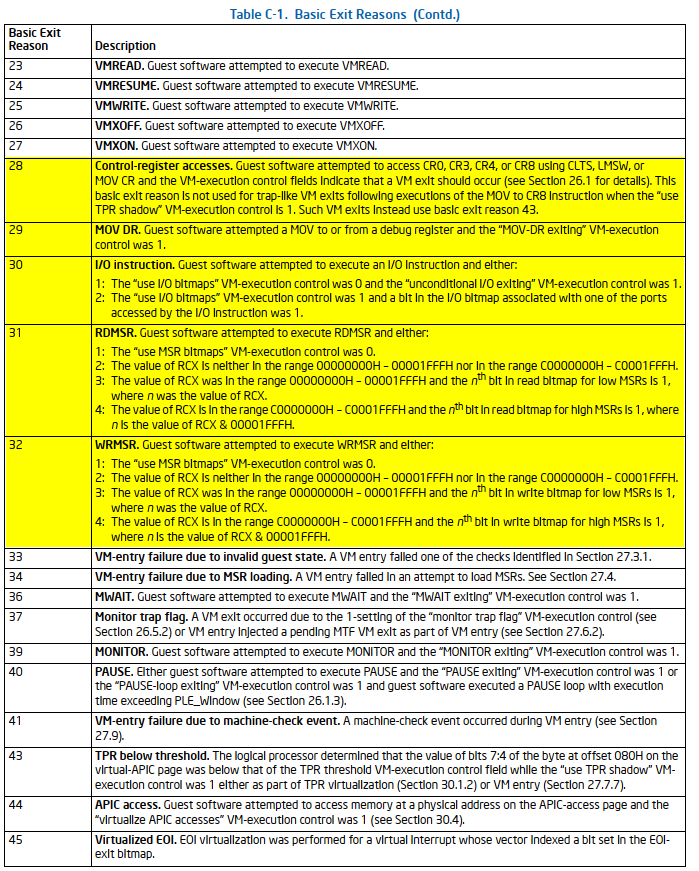

v4 = ((readmsr(IA32_VMX_BASIC) >> 0x20) >> 0x17) & 1; // [1]

v5 = readmsr(v4 != 0 ? IA32_VMX_TRUE_ENTRY_CTLS : IA32_VMX_ENTRY_CTLS); // [2]

v6 = v5 | WORD2(v5) & 0x204; // [3]

v7 = readmsr(v4 != 0 ? IA32_VMX_TRUE_EXIT_CTLS : IA32_VMX_EXIT_CTLS); // [4]

v8 = v7 | WORD2(v7) & 0x8200; // [5]

v9 = readmsr(v4 != 0 ? IA32_VMX_TRUE_PINBASED_CTLS : IA32_VMX_PINBASED_CTLS); // [6]

v10 = readmsr(v4 != 0 ? IA32_VMX_TRUE_PROCBASED_CTLS : IA32_VMX_PROCBASED_CTLS); // [7]

v88 = v10 | HIDWORD(v10) & 0x92808000; // [8]

v11 = readmsr(IA32_VMX_PROCBASED_CTLS2); // [9]

v89 = v11 | HIDWORD(v11) & 0x10102E; // [10]

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(PIN_BASED_VM_EXEC_CONTROL, v9); // [11]

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(CPU_BASED_VM_EXEC_CONTROL, v88);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(VM_EXIT_CONTROLS, v8);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(VM_ENTRY_CONTROLS, v6);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(SECONDARY_VM_EXEC_CONTROL, v89); // [12]

CurrentProcessorNumber = KeGetCurrentProcessorNumberEx(NULL);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(VIRTUAL_PROCESSOR_ID, CurrentProcessorNumber + 1);

v35 = sub_1400026A8(fhv_ctx->ept);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(EPT_POINTER, v35);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(EXCEPTION_BITMAP, 2);

PhysicalAddress = MmGetPhysicalAddress(fhv_ctx->fhv_bitmaps->another_bitmap_1); // [13]

v33 = MmGetPhysicalAddress(fhv_ctx->fhv_bitmaps->another_bitmap_2); // [14]

v34 = MmGetPhysicalAddress(fhv_ctx->fhv_bitmaps->msr_bitmap); // [14]

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(IO_BITMAP_A, PhysicalAddress.QuadPart); // [15]

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(IO_BITMAP_B, v33.QuadPart); // [16]

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(MSR_BITMAP, v34.QuadPart); // [17]

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(VMCS_LINK_POINTER, 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF);

v36 = readmsr(IA32_DEBUGCTL);

vmwrite_rcx_rdx(GUEST_IA32_DEBUGCTL, v36);

/* ... (code omitted for brevity) ... */

}